Source Wiki Commons. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Papaver somniferum

Addiction, a Technology Mediating China and Europe

By looking at opium at a historical intersection between Western European culture and Chinese tradition, philosopher Paul Boshears examines how various concepts of addiction have come to define human relations to things—including the world itself—and frame our understanding of what human intelligence can be.

If we think of substances and practices that are said to be addictive—certain types of drug, video poker, and so on—as possessing an agency to which users or practitioners submits themselves, we are thinking of them as something like an alien intelligence. Frustratingly, what intelligence “is” is generally assumed to be recognizably like the human mind. So, when searching for alien intelligences or artificial intelligences, the assumption is that intelligent beings will reveal themselves in a universally recognizable way. This is the flaw of a certain kind of panpsychism, which assumes that minds are universally the same. But we know that our own minds are the result of our brain’s processing the sensory data our organs are designed to register. Would we be able to recognize intelligent behavior from an organism whose mind is the result of some other process?This is the question Ian Bogost asks in “What If Thinking Machines Are Already All Around Us?,” Edge, 2015, http://edge.org/response-detail/26211. This question of intelligibility is a familiar question for those who study culture. In its simplest terms, culture is the concept used to discuss what humans choose to do with things. The substantial differences between cultures are, in essence, technological ones.

There are no nouns in nature, to paraphrase philosopher Ernest Fenollosa, isolated from one another in an empty space; rather, there is a complex of related materials that differentiate themselves in the performance of their relating to one another.Ernest Fenollosa and Ezra Pound, The Chinese Character as a Medium for Poetry: A Critical Edition, ed. Haun Saussy, Jonathan Stalling, and Lucas Klein. New York: Fordham University Press, 2008, pp. 51–52. To think of what a substance is is to think about the nature of “things.” Things are the meeting points. They are coterminous and intelligible insofar as they are this particular thing here when they are not being that particular thing over there. In Northern European languages and almost silently in English, we still have vestigial elements that illustrate this orientation toward the universe: the legislative bodies of several Scandinavian governments convene to form an Alþingi, or its cognates the Folketing and Storting—the people’s house, the great assembly.See Gísli Pálsson, “Of Althings!” in Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (eds.), Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005, pp. 250–57. In the United States, a politician’s speech before a gathering of voters is a “stump speech,” but in the United Kingdom it is a “husting” (house thing). This “house thing” is the place where we gather, and based on what our meeting affords, we act. It is possible to recognize a similar impulse in the term “cohort,” from the Latin co- and hortus, which describes the band with whom we share our garden. “Substance” points toward the essence of a thing, and we claim to have the “gist” of the matter—but gist is ultimately the place where we lay down. Gist, the habitual place of resting for birds, comes to the English language through the Old French gîte, itself from the Latin jacēre, I throw, as in Caesar’s famous Alea iacta est (“The die is cast”) at the crossing of the Rubicon. Oxford English Dictionary, “gist”; Dictionnaire de l'Académie française, “gésir”; Dictionnaire illustré latin-français.

Within those walls we are cultured and cultivated and mutually formed by the company we keep.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

Lest the reader argue that this etymological foray was immaterial, allow me this defense: substantiating a claim is to corroborate the evidence, which requires establishing a relationship between the testimonials. “Etymology” itself is derived from the Greek étumos, that is, what is true or real.

There is no genuinely alien cultural project. As we become conversant in the ways in which a culture is practiced, we find what philosopher Thomas Kasulis refers to as “holographic entry points” into that culture.Thomas P. Kasulis, Shinto: The Way Home. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2004, 20. The ways in which we understand our relationships to things enables us to pass through the gates of unknowing and thereby effect our own reorientation.

A contemporary analogue of “substance” in Chinese is wuzhi (物質), as expressed in a phrase like huaxuewuzhi (化學物質, “chemical substance”). Lest we be too comfortable with this seemingly straightforward translation, let us examine what is at work in those Chinese characters. With the first pairing, huaxue (化學), we see that the characters can mean what is intended by “chemistry,” but the phrase literally refers to the “study of changes.” But the phrase huaxue (化學) did not originate in China; it was introduced by the Protestant missionaries in the second half of the nineteenth century with the publication of the London Missionary Society’s Shanghai Serial. The next character, wu (物), means “thing.” Since ancient times, the synecdoche wanwu (萬物, literally, “ten thousand things”) has connoted all matters in the cosmos. But what kind of thing is being referred to in this instance? Here we are referred to the kind of thing that is zhi (質), which can indicate “matter” as well as “hostage,” as in the phrase renzhi (人質), or to pawn. Such a potent material, one that could hold us hostage, that places us in the debt of another. At the same time that these Protestant missionaries were coining this terminology, another was also being generated: “addiction.”

Originally coming from a Latin legal term, to be addicted was to be indentured, being literally spoken for in advance (ad + dictus) because of a debt one owed to another. The impulse toward the measurement of human behavior and physiology in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—such as in the nascent social sciences of anthropology, sociology, criminology, etc.—was simultaneously also the measurement of cultural differences.See, for example: Peter K.J. Park’s Africa, Asia, and the History of Philosophy: Racism in the Formation of the Philosophical Canon, 1780–1830. Albany: SUNY Press, 2013. Michael Adas, Machines as the Measure of Men: Science, Technology, and Ideologies of Western Dominance. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014. Justin E.H. Smith, Nature, Human Nature, and Human Difference: Race in Early Modern Philosophy. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2015. These deviations among peoples informed and justified the codification and medicalization of human behaviors. To the extent that we can construct any coherent account of what is meant by the term “addiction” in English, a coherent conversation with China is required. In order for that conversation to take place, it will have to be mediated by opium, the fundamental hinge upon which the early relationships between China and the European West pivots.

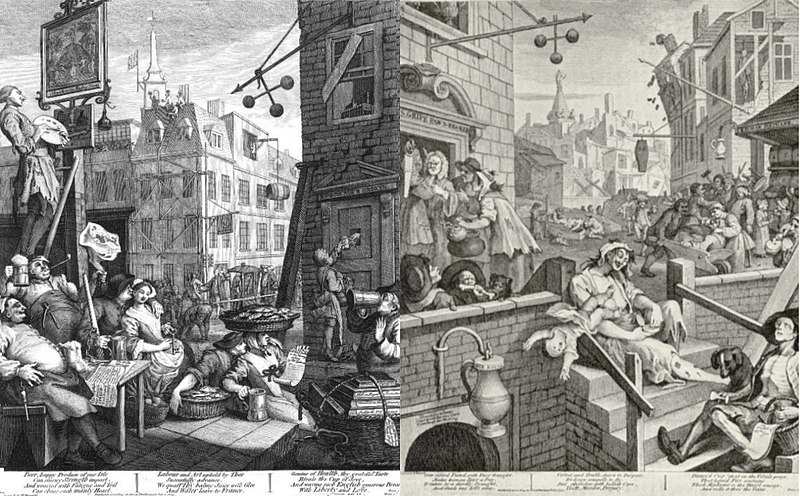

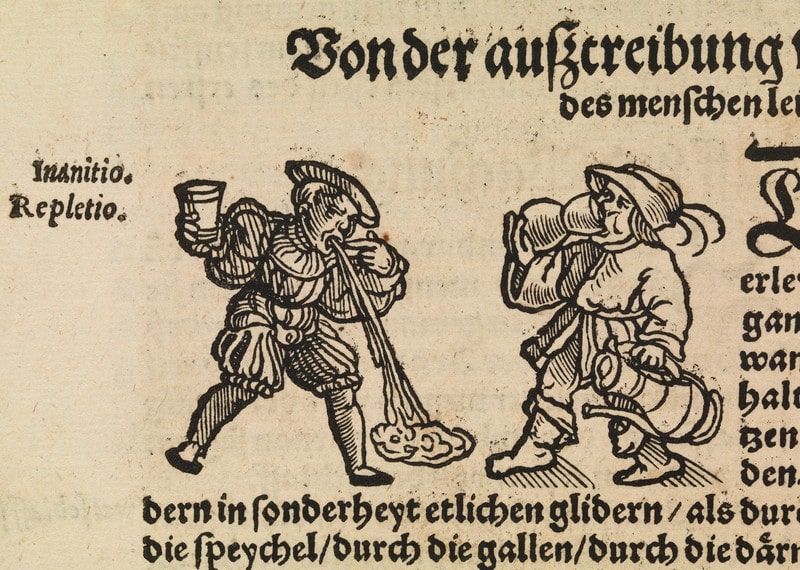

Drug historian David T. Courtwright describes the era of discovery and dissemination of the world’s psychoactive resources (tea, coffee, opium, tobacco, coca, distilled spirits) as the “psychoactive revolution.”David Courtwright, Forces of Habit: Drugs and the Making of the Modern World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001. It is along class lines that revolutions in social habit were formed and reinforced in the wake of the psychoactive revolution. As costs decreased for coffee and tea (through the further refining and perfecting of mechanical processing) and sugar (thanks to the further perfecting of the chattel slave trade), what were once stimulant delivery technologies exclusively available to the aristocracy became more readily available to the working classes. And as bread and coffee and tea became more prevalent as the breakfast foods of workers, the days of the “ploughman’s breakfast,” based on low-alcohol beer, were growing short, and the further addition of sugar and milk meant the loss of calories previously consumed through the home-brewed beer could be recouped through the caffeinated beverages.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

With the introduction of alcohol distillation technologies into Europe in the sixteenth century, caffeine and alcohol came together to stimulate and motor a flourishing drinking culture. To illustrate the extent to which European culture had become a drinking culture, philosopher Herbert Fingarette reports that throughout the eighteenth century the average colonial American consumed four gallons of alcohol per year, compared to the two and a half being consumed two centuries later.Herbert Fingarette, Heavy Drinking: The Myth of Alcoholism as a Disease. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989, p. 14. When the English first became familiar with tobacco use from the “New World,” the idea of consuming tobacco could only be understood as “drinking” tobacco rather than “smoking” it.

A contemporary conception of global commodity trade was born with the central role opium played in the European colonial era.

Click here to insert text for the typewriter

The Chinese term for opium is yapian (鴉片), likely from the Arabic or Persian, and from this journey to China we’ve received into the English the term “yin,” meaning to crave, likely from the Chinese yin (癮), meaning addiction.Keith McMahon, The Fall of the God of Money: Opium Smoking in Nineteenth-Century China. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002, p. x. No one is born with an innate knowledge of how to procure, manufacture, or consume opium; rather, one must undergo an apprenticeship in drug use—that is to say, addiction requires a social network.With this fundamental sociality required for addiction to be possible, let us note that when wishing to address a group in the Pittsburgh area of the United States, a group of others is summoned as “Y’ins.” But in China during the nineteenth century, opium was more commonly called yangyan (洋煙), the “Western smoke,” and this lexically implicate Europeans, the yangren (洋人), or “people from the West.”Although it should be pointed out that yang (洋) did not come to mean Europeans until the middle of the nineteenth-century; see McMahon, The Fall of the God of Money, p. 29n3. Indeed, for Europe, China itself was a master object, a drug to be taken.

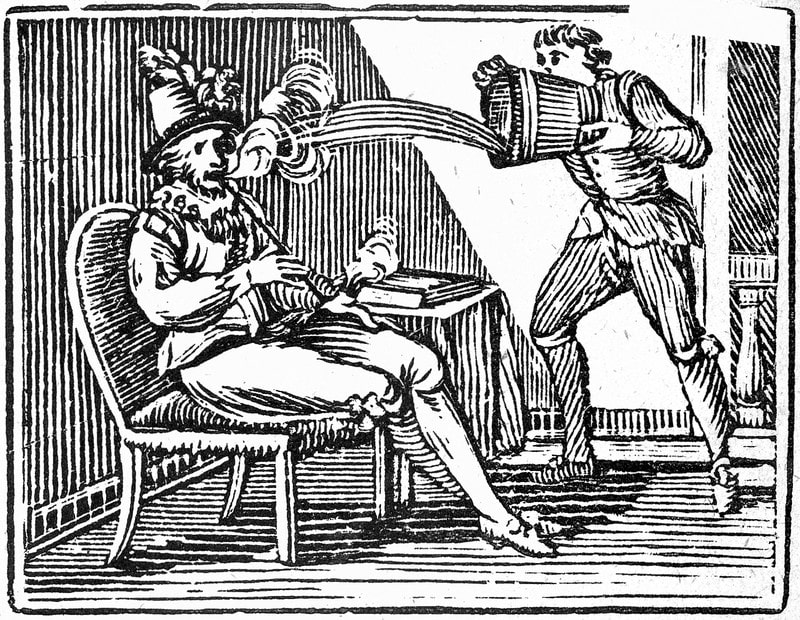

From the seventeenth century until the twentieth century, Britain was awash with opium, but it was the manner in which opium was consumed—the technical apparatuses, the postures, the clothing one wears when consuming opium—that marked the Asian as inferior to the European (even the drunkard was seen as more wholesome in comparison to the gender-bending, robe-wearing, opium-besotted Asian).McMahon states, “The debate that pitted opium against alcohol, in short, tied in with the debate that distinguished the remote and self-satisfied Chinese—who are ‘effeminate’—from the outgoing and progressive Europeans—marked as masculine.” McMahon, The Fall of the God of Money, p. 3. The Chinese smoked opium; the British ate it in the form of laudanum. To the British observer, smoking was a luxuriant use of the psychoactive resources. Drinking laudanum was different: it was the proper technique for presenting the poison as a medicine. Chinese opium smoking was a site for sociality whereas an opium fiend like Thomas De Quincey maintained his solitude. The Chinese reclined when they smoked, the European was upright. The concept of addiction was forged in a cross-cultural dialogue between the European West and China.

We have a tendency to think of the transmission of germs, crops, and languages when thinking about the earliest phases of globalization, but what about the seemingly immaterial habits by which someone does something? The concept of cultural techniques, or kulturtechniken, developed among German media theory circles, describes the processing operations that coalesce into entities that then come to be thought of and reacted to as agents running those very same processes.Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, “Cultural Techniques: Preliminary Remarks,” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 30, no. 6 (2013), p. 11. As the concepts of race and modern medicine developed in the European colonial expansion, we can see how these fields of knowledge became significantly informed by the confrontation between two modes of cultural techniques for consuming opium: in the distinction between drinking culture (Western Europe) and smoking culture (the Americas and East Asia).

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The mark of being human is the mediation of our relationships to the universe through technologies and techniques. Our cultural practices are, essentially, our collective decisions to interface with things in a place. We become habituated to the effects caused by our techniques and technologies; they are our second nature. Through our uses of techniques and technologies, we come to understand ourselves in our habitat. More simply, our habitat’s where our habit’s at.

Addiction names a relationship between humans and technologies. Those technologies can be designed drugs, like marijuana and meth, or they can be designed interfaces like gambling at a poker table or video poker. It seems to me that one’s relationship to an object of addiction is a matter of habit and technical mastery. For example, one learns to “hold their liquor,” how to more adeptly inhale from a bong, how to gamble with greater aplomb. Underlying the logic of addiction is this question: What is the appropriate relationship to these technologies and media? Do we consume opium to replenish our qi (氣) and thereby become “hackers” of our shen (腎) circuit, as has been argued in traditional Chinese medicinal practices? Or is it the case that opium has an agency of its own, to which we cannot help but submit ourselves? Both positions are idealized and political, demanding a uniformity and consistency that is untenable. The majority of drug use is less than ideal—people forget to take their birth control, folks “mature out” of cocaine habits, grandmothers end text messages with “Love, Grandma.” The rhetoric of addiction masks this so-called vernacular use of these technologies,See Jacob Gaboury’s manifesto “On Vernacular Computing,” Art Papers, vol. 39, no. 1 (2015), pp. 42–43, and Brian Droitcour, “Vernacular Criticism,” New Inquiry, July 24, 2014, http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/vernacular-criticism. assuming that all use is ideal use. The inherent message is that people are stewards of their physical-moral corpus and fail to observe the rules governing proper use of technologies designed around them.

Lacking mind, all things are dumb. But as we’ve just seen above, we know things are dumb because they don’t communicate to us. Unlike things, we are smart and can look into things and understand that they are actually really interesting. To paraphrase philosopher and psychologist William James, we’re the dumb clods if we neglect to identify those facets of things that are so wondrous.William James, “Making a Life Significant,” in Talks to Teachers on Psychology and to Students on Some of Life’s Ideals. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2001, p. 130. But what if there are some things that are actually smart and they’re trying to overcome us? It’s group entertainment to imagine computers and super apes revealing themselves to be secretly smart (“We should have known!”), and could we also imagine that other things like opium alkaloids are also secretly smart and trying to overcome us? Or ponder whether or not animals have addictions?

When I think about addiction, I tend to think of it as a human relationship to a technique or technology. The gateway-drug rhetoric points toward the career one cultivates in drug use but also masks the reciprocal action of the technology called “gates.” Gates disclose a relationship, not simply enclose a space. As historian and media theorist Geoffrey Winthrop-Young states,

We emerged, quite literally, from doors and gates.Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, “The Kultur of Cultural Techniques: Conceptual Inertia and the Parasitic Materialities of Ontologization,” Cultural Politics, vol. 10, no. 3 (2014), p. 387.

To the extent that the space is enclosed, what we better understand is that certain modes of relating between two entities are possible. How does this inflect our understanding of so-called gateway drugs?

In The Gateless Gate (Wumenguan, 無門關), we read an exchange between a Buddhist monk and Zhaozhou (Joshu in Japanese) in which the question is asked,

Does a dog have Buddha nature or not?

The famous response is, of course,“ wu (無),” which is a negation, but not a verb. In so responding, Zhaozhou avoids being ensnared in an essentialist argument; he is, in the words of philosopher Peter Hershock, able to

close the wound of existence.Peter D. Hershock, Chan Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2005, p. 85.

If I want to understand how a dog has Buddha nature (and the non-locality of Buddha nature), I have to scrap my attachment to being the sole possessor of what I assume is mind. And I have to scrap my attachment to what I believe a mind can perceive. Currently, how humans ought to relate to things is in part predicated on how intelligent a thing reveals itself to be to humans. If we arrest the habit of seeking human minds in things and instead try to relate to the experiences things undergo, might we have more robust and useful relationships with the cosmos?

Or is it the case that “mind” is an adequate term for grounding what makes being human so special? So utterly drunk on our own self-regard about the cosmic value of our intelligence, we experience moments of inebriation that throw us into questioning our assumptions about what sobriety actually is. Psychedelic experiences might be examples of this, but these moments of mind-annihilating sobriety can also accompany the use of other techniques, like sitting meditation, or spinning, or breathing. Is it possible to have a kind of relationship with technologies (which are of course kinds of things) beyond the self-regarding assumption that human minds are the yardstick by which intelligence ought to be measured?

small

align-left

align-right

delete