Source: Breuil, H. and M.C Burkitt (1929). Rock Paintings of Southern Andalusia. (Oxford)

Sound and Pain

One cardinal source of the trauma induced by the technosphere is sonic: the ubiquity of anthropophonic vibrations passing through our environments. Social scientist and artist Josh Berson tells his story of being caught by the pervasiveness of human-generated sounds, forever beholden to a tinnitus of life emanating from our remaking of the Earth’s resonator.

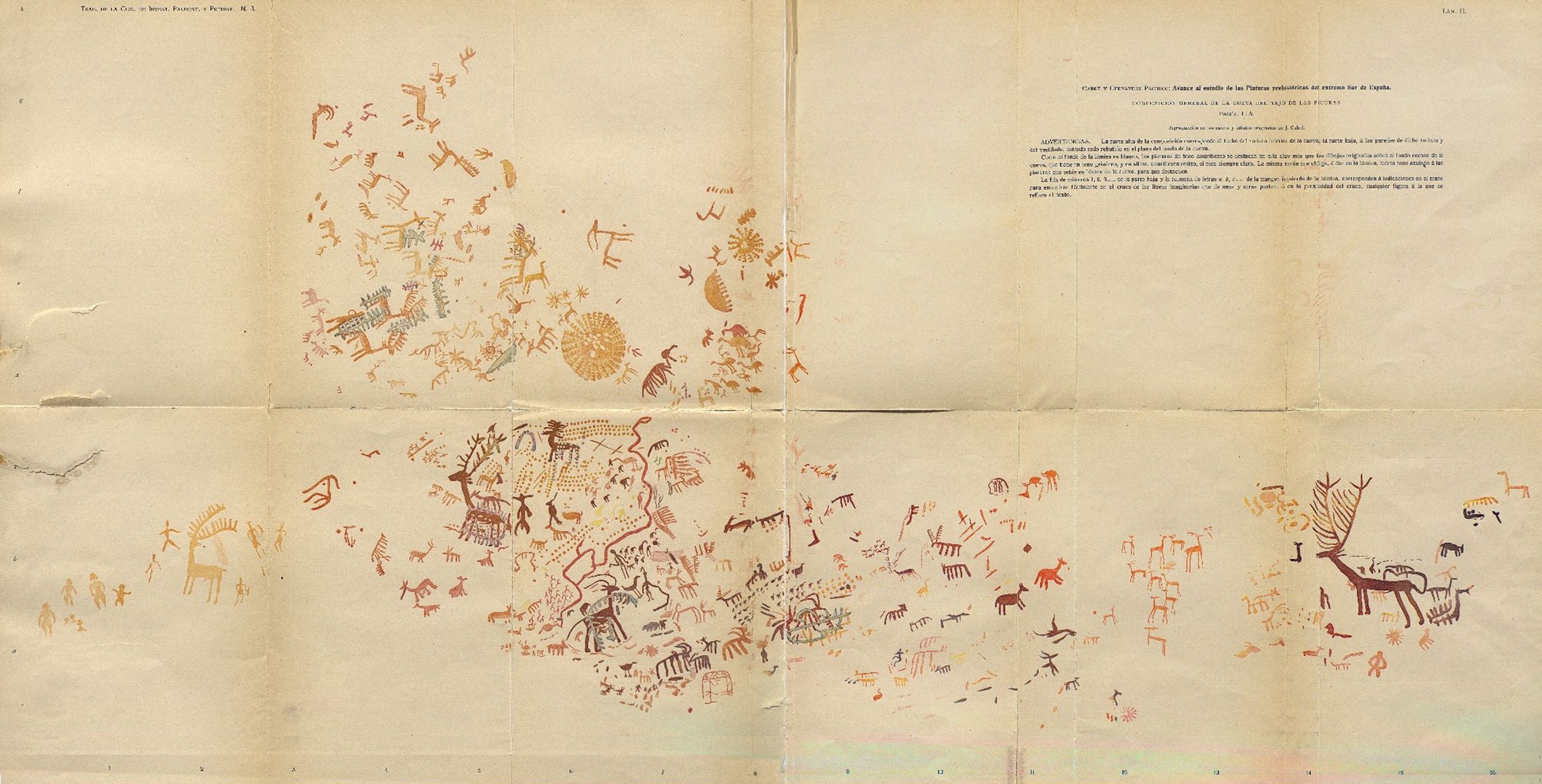

I want you to imagine you are standing on a beach watching the sun go down. It is 15,000 years ago. The only sounds are the crash of the surf, the calls of gulls and kingfishers, the wind in the salt grass, and the snap of dry tinder from a campfire up the slope leading down to the water. This could be what now is the Atlantic coast of Portugal, it could be the Dampier Peninsula in the northwest of Australia—both saw human occupations at this time. If this were 10,000 years ago, it could be the coast of British Columbia. It does not much matter. The sun slips below the horizon. The color drains from the sky and it begins to get dark. There are, of course, other kinds of sensations here. From the campfire comes the scent of fish cooking, the astringent notes of fat and muscle combusting, mixed with the saline alkalinity that hits your nasal membranes when you inhale. But our main concern is with how things sound. The light is gone. Above, the stars begin to appear, a country unto themselves, its landmarks as familiar as those of the earth by day. The sea, by contrast, is a vision of oblivion, an implacable, all-ablating presence, its rote hypnotic and terrifying. You take a step forward. The tide is coming in, and the water flows up to meet you. Then, from the fire comes the hoarse quaver of a flute. You turn from the sea and toward the reverberant huuing that is not like any other sound.Elizabeth C. Blake and Ian Cross, “The acoustic and auditory contexts of human behavior,” Current Anthropology 56, no. 1 (2015): pp. 81–103; Margarita Díaz-Andreu, Carlos García Benito, and Maria Lazarich, “The sound of rock art: The acoustics of the rock art of southern Andalusia (Spain),” Oxford Journal of Archaeology 33, no. 1 (2014): pp. 1–18; Juan José Ibáñez, Jesús Salius, Ignacio Clemente-Conte, and Narcis Soler, “Use and sonority of a 23,000-year-old bone aerophone from Davant Pau Cave (NE of the Iberian Peninsula),” Current Anthropology 56, no. 2 (2015): pp. 282–9; Rita Dias, Cleia Detry, and Nuno Bicho, “Changes in the exploitation dynamics of small terrestrial vertebrates and fish during the Pleistocene–Holocene transition in the SW Iberian Peninsula: A review,” Holocene 26, nos 1‒2 (2016): pp. 964–84.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Keep this scene in mind as you read the following, which appeared in The Lancet on October 10, 1908:

A woman, aged 49 years, was sent to me by Mr W. G. Sutcliffe of Margate on 14 November 1906. Her illness commenced suddenly in February, 1906, with buzzing tinnitus, vertigo and nausea, and on several subsequent occasions a similar attack occurred. After a time the tinnitus became continuous and was more and more often accompanied by giddiness. No benefit was derived from medical treatment nor, was benefit derived from staying at Margate [a sea resort on the southeastern coast of England] and the Isle of Wight. In September, 1906, the character of the tinnitus suddenly changed from a buzzing to a most distressing steaming or whistling noise which, at its height, became actually painful; the patient’s own expression was ‘the noise is the pain’. When I saw her on November 14,1906, about ten months after the commencement of the illness, she complained of intolerable tinnitus in the right ear, occasionally accompanied by giddiness and nausea. She was in great distress and feared that if no relief could be given she would go mad and kill herself. The right ear was almost totally deaf; the watch and the voice were not heard at all and the tuning fork was scarcely perceived. The tympanic membrane looked normal. There were no signs of a gross intracranial lesion; the disease was clearly labyrinthine. I suggested division of the auditory nerve but advised the patient first to consult Dr D. Ferrier. I did not see her again until January, 1908, when she came to me with Dr Soden. In the interval she had been under Dr Ferrier, Dr Purves Stewart, Mr Lake, Mr Woods, and others. Many methods of treatment, including hypnotism and high-frequency currents, had been tried. In November, 1907, Mr Lake removed the semicircular canals of the affected side; this operation almost completely relieved the patient from the vertigo but in no way affected the painful tinnitus. Facial palsy followed Mr Lake’s operation but from this there were signs of commencing recovery. The general condition was not good; the patient was feeble, fat, and flabby, and the pulse, for some reason or another, varied from 100 to 120. I renewed my original suggestion that the auditory nerve should be divided and this was now agreed to by Dr Ferrier.Charles A. Ballance, “A case of division of the auditory nerve for painful Tinnitus,” The Lancet 172 (October 10, 1908): pp. 1070‒3.

The operation was performed in two stages, the first to remove a section of the temporal bone, the second, nine days later, to section the auditory nerve. Upon awakening from anesthesia, the patient demonstrated modest signs of cranial nerve injury: lateral nystagmus of the eyes to the left (that is, contralateral to the operated side), deviation of the tongue to the left, paresis of the right side of the face and pharynx—and, of course, complete deafness of the right ear. Over the next four months, the facial and pharyngeal symptoms partly abated. The tinnitus was gone. The surgeon, Charles Ballance, thought the prognosis good. He compared sectioning of the cochlear branch of the eighth cranial nerve for tinnitus to sectioning of the fifth nerve for trigeminal neuralgia (tic douleureux).

Ballance was a highly regarded vascular and neurosurgeon, and while auditory nerve sectioning had been attempted before, his technique and outcome were new. But it is difficult to know what to make of his report. Today, sectioning of the cochlear nerve is contraindicated for tinnitus, since it amounts to deafferentation—the removal of input from a sensory system. In fact, tinnitus arising from sensorineural hearing loss responds well to cochlear implants—the reintroduction sensory input previously lost.

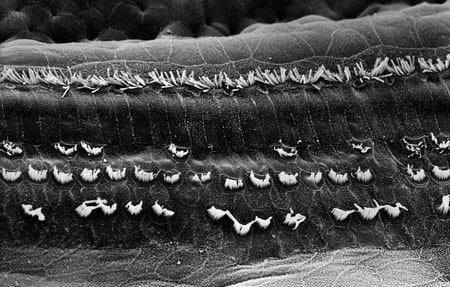

In most cases, tinnitus seems to originate with a plastic response in the dorsal aspect of the cochlear nucleus (DCN), the part of the brainstem most focally implicated in hearing, to deafferentation in the cochlea. The ablation of hair cells in the cochlea, whether via exposure to noxiously loud sound or the cumulative sensory and oxidative stresses of aging, removes inhibitory stimulation from the regions of the DCN that code for the same characteristic frequencies as the ablated cells. This promotes increased spontaneous firing rates, increased firing synchrony, and increased bursting of action potentials among excitatory neurons in those regions. An enhanced tendency toward spontaneous excitatory bursting is propagated, via spike-timing-dependent plasticity, to the limbic and cortical structures that subserve auditory object perception, so that the auditory system effectively learns a phantom percept. By and large this is anti-Hebbian learning: downregulation of inhibitory inputs to postsynaptic excitatory neurons strengthens frequency-specific excitatory pathways, in part via reuptake modulation of excitatory neurotransmitters. Tinnitus is also associated with enhanced functional connectivity (that is, coactivation) between the auditory cortex and the parahippocampal region, suggesting that it represents a kind of Bayesian estimation. This means that in the absence of reliable peripheral input for a particular frequency range, the auditory system relies on memory; that is, the nervous system’s history of past sensory experience, to fill in the gaps.Susan E. Shore, Larry E. Roberts, and Berthold Langguth, “Maladaptive plasticity in tinnitus: Triggers, mechanisms and treatment,” Nature Reviews Neurology 12 (February 2016): pp. 150–60.

In the case described above, the tinnitus seems to have been at least partly a product of Menière’s syndrome, the instigating peripheral damage likely caused by a viral infection of the semicircular canal, perhaps exacerbated by preexisting deafness, and not by exposure to loud sound. As a rule, Ballance’s solution should not work, and the case has little to say about the painful dimensions of sound—not audition, the phenomenal dimension of a sensory system, but sound as an acoustic phenomenon, the oscillatory compression and rarefaction of air and other media in the world. It is sound in the acoustic sense that I want to focus on. What drew me to Ballance’s report was the patient’s distress—“the noise is the pain.” This distress, the distress of constant, ineluctable exposure to noxious sound, so that the sound becomes laminated to the pain it causes, is uniquely anthropogenic—not uniquely human in its experience, but in its causes.

The fact that music is intrinsically satisfying is often held up as one of the great mysteries of human experience, but the more we learn about the evolutionary and functional sources of music’s pleasurable nature, the clearer it is that these are not unique to humans. The tendency to groove, to spontaneously entrain to a rhythmic pulse, has emerged a number of times in animal evolution—and, if we slow time down, so that the duration of a beat becomes that of a day, we can see that it is not so different from other forms of rhythmic entrainment common to plant and animal modes of sensing.Josh Berson, “Cartographies of Rest: The spectral envelope of vigilance,” in Felicity Callard, Kimberley Staines, and James Wilkes (eds), The Restless Compendium: Interdisciplinary Investigations of Rest and Its Opposites. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, pp. 91–8. Neither is improvisation in pitch series limited to humans.Hollis Taylor, “Blowin’ in Birdland: Improvisation and the Australian Pied Butcherbird,” Leonardo Music Journal 20 (2010): pp. 79–83.

What is uniquely human is the tendency to construct acoustic environments that are abidingly painful, or at least unpleasant. In part, this is an outcome of sound’s unique relationship to pain. When a smell causes an aversive reaction, we don’t think of it as painful—disgusting, but not painful. Optical stimuli can be painful, but in the absence of photophobia—generally a product of inflammation in the eyes—it takes significantly more gain in the optical signal before we call it painful. By contrast, painfully loud sounds are common, and you don’t need any particular inflammatory condition of the cochlea to experience them as such.

Sound represents a highly refined form of touch, the basilar membrane of the cochlea serving as a tonotopic amplifier for the vibratory pressure of air compression and rarefaction on the tympanum, and this may have something to do with the fact that sounds can be noxious—painful—in a way optical and olfactory stimuli generally cannot. (Among the recent findings in the functional anatomy of tinnitus is that deafferentation in the cochlea leads to upregulation of somatosensory inputs to the cochlear nucleus, so that tactile and enteroceptive sensations come to exert greater influence—of what kind is not known—on activity in the cochlear nucleus.)

large

align-left

align-right

delete

But, of course, it is not just that sound is intrinsically easier to construe as painful; it is also that we manipulate our acoustic environment, and that of the other living things with which we share space.

Among humans, the earliest instruments of organized sound-making were the voice and the hands, and then perhaps came lithic implements—handaxes, choppers, scrapers, the core-and-flake artifacts of the Acheulean industries, whose horizon spanned more than a million years from the earliest dispersals of Homo erectus out of East Africa through the appearance of archaic humans in the sapiens and neandertal clades. In A Million Years of Music, Tomlinson sketches an Acheulean “taskscape” in which the percussive sounds of flake production reinforced the cooperative character of lithic manufacture and food preparation, providing a tactus, a metrical pulse, tink tink tink—something for individuals to entrain to. At a later date, enclosures bordered by exposed rock surfaces came to serve as resonators, channeling the anthropogenic sound created within them. These spaces acquired special significance, perhaps as places for carrying out increase rituals, something attested in the rock art that is prominently associated with highly resonant sites.Díaz-Andreu et al., “The sound of rock art.” But it was the control of proteinaceous materials—bone, antler, wood, reed, hide, hair, nerves, and, at length, silk—that most radically transformed the human capacity to produce time-bounded—episodic—acoustic environments.

With protein-based materials, humans could create a wider range of resonators: wider in pitch range, in timbral characteristics (overtone series, spectral envelope), and wider and suppler in the range of affordances these resonators offered for controlling pitch, dynamics, timbre, and the attack-decay-sustain-release envelope. With the emergence of organic resonators—bone aerophones such as those found in eastern and western Eurasia from 30,000 years ago—we can begin to imagine, however tenuously, made sound in the way we think of it today.Ibáñez et al., “Use and sonority.”

The capacity to create episodic acoustic environments is focally implicated in the capacity to reliably induce the marked states of being that have been ubiquitous in the history of medicine down to the present (think of eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing, or ASMR, to give two contemporary examples Debra Stein, Cécile Rousseau, and Louise Lacroix, “Between innovation and tradition: The paradoxical relationship between eye movement desensitization and reprocessing and altered states of consciousness,” Transcultural Psychiatry 41, no. 1 (2004): pp. 5–30; Emma Barratt and Nick Davis, “Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR): A flow-like mental state,” PeerJ 3: e851 (2015), doi 10.7717/peerj.851.). By now we understand—a bit—how driving rhythms, whether on the Acheulean taskscape or in a gym or dance club, work to create states of heightened absorption and suggestibility—trance—in the individual and kinesthetic entrainment—Durkheim’s “collective effervescence”—in the group.Josh Berson, Computable Bodies: Instrumented Life and the Human Somatic Niche (London: Bloomsbury, 2015). M. Elamil, J. Berson, J. Wong, L. Buckley, and D. Margulies, “One in the dance: Musical correlates of group synchrony in a real-world club environment,” PLoS ONE (forthcoming). But driving rhythms are just one dimension of how we shape our acoustic environment. The role of others, particularly manipulations of timbre, in shaping motor vigilance and mood remain poorly understood.Berson, “Cartographies of Rest.”

The shift to a biosphere dominated by anthropophony—human-generated sound—represents a change potentially farther-reaching than the introduction of ubiquitous artificial light. It is easy to point to urbanization as the main vector of change in the modal acoustic environment for humans and our cohabitant species.Hans Slabbekoorn and Ardie den Boer-Visser, “Cities change the songs of birds,” Current Biology 16, no. 23 (2006): pp. 2326–31. But urbanization is just part of the story. We are also witnessing—more than witnessing, causing—a dramatic, global turnover in biome structure, from forest mosaic to open scrub and agricultural land.Erle Ellis, “Ecology in an anthropogenic biosphere,” Ecological Monographs 85, no. 3 (2015): pp. 287–331; Craig Allen, David Breshears, and Nate McDowell, “On underestimation of global vulnerability to tree mortality and forest die-off from hotter drought in the Anthropocene,” Ecosphere 6, art. 129 (2015): p. 129. If you think of the Earth’s surface as a resonator, it is not just that we are introducing new sounds into the resonator. We are also remaking the resonator itself, and remaking it, by and large, in the direction of greater reflectance and greater spectral spread. We are creating environments more conducive to the high-frequency broadband sound sometimes called urban drone. Does this mean we are all at risk for long-term threshold elevation—a kind of numbing effect, an attenuation of our capacity to pick out low-intensity sounds in these frequency bands, which might contribute to tinnitus? Who knows. It’s plausible as a hypothesis, but the long-term effects of ongoing exposure to broadband sound below the threshold of pain are poorly understood and difficult to model in the laboratory.Xiaoming Zhou and Michael M. Merzenich, “Environmental noise exposure degrades normal listening processes,” Nature Communications 3, art. 843 (2012): 843, doi: 10.1038/ncomms1849. In order to study them in the world we would need a much more precise vocabulary for describing the painful qualities of sound, something more than “The noise is the pain.”Cf. Shigeshi Kuriyama, The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine. New York: Zone Books, 1999, pp. 46–9.

At this point, the standard move would be for me to say that, in fact, there is no difference of kind between anthropophony and other kinds of biophony, nor, indeed, between biophony and geophony (sounds of wind, water, etc.)—that is, to point out the brittleness of efforts to split off culture from nature. But I’m not interested in differences of kind. I’m interested in differences of degree. And once we start asking about differences of degree, we can formulate testable claims about grade shifts between the qualities of different kinds of sounds. By grade shift, I mean this: imagine a scatter plot with a regression line summarizing the trend between the two dimensions of the plot. Let’s say the points on the plot represent sounds, and the X dimension organizes those sounds according to some acoustic feature. It could be intensity. It could be fundamental frequency. It does not much matter. The Y dimension organizes the sounds according to how painful they are. Imagine whatever procedures you wish for assessing painfulness. So now, we have a slope relating painfulness to some characteristic of the sound. Some of the points on the plot represent sounds arising from human activity. Others represent sounds not arising from human activity. Again, if this seems too brittle, imagine not two categories but ten, a gradient of human causation. Now watch as points fade out, leaving only those with greater human causation. As the plot thins out, the regression line rises—across the board, sounds are more painful.

If this strikes you as crude and tendentious, of course it is. Lying awake at four in the morning, I am struck by how my own tinnitus—unilateral left, my one hearing ear, usually a reedy whistling at about 10,000 Hz—resembles the chirping of insects on Hiroki Sasajima’s Colony (2012).Hiroki Sasajima, Colony, audio recording: Impulsive Habitat, 2012, ihab040 [online](http://www.impulsivehabitat.com/releases/ihab040.htm). Hiroki’s work exemplifies a subgenre of ambient music where the sound consists in minimally processed field recordings and part of the pleasure of listening comes from picking out where the artist has diverged from the source material. Hiroki’s insect recordings were made with recording devices left out overnight in weatherproof enclosures in places with little to no human-generated sound.Cathy Lane and Angus Carlyle, In the Field: The art of field recording. London: Uniformbooks, 2011. If you lie on the floor with your eyes closed, listening, you could imagine yourself to be lying in a clearing in a wilderness reserve, late at night. If these recordings resemble tinnitus, then clearly what is painful about tinnitus is not just its spectral envelope but also the context in which we experience it. And indeed, it is possible, with practice, to dissociate the sound of tinnitus from the pain of it, and this has been found to be more effective than other treatments (pharmacological, transcranial magnetic stimulation) that target the neurological dimensions of phantom sound directly.Shore et al., “Maladaptive plasticity in tinnitus,” p. 156.

All the same, we had better start thinking more clearly about the relationship between sound and pain. We spend our lives bathed in sound, all of us—Deaf and hearing alike—when we are sleeping no less than when we are awake, we are alive to the ongoing vibratory fluctuations of pressure in the air, water, and viscous gels that make up our environment. Asphalt and glass, wood and rubber, polycarbonate and steel, earth and stone, the tissues of our bodies and those of other living things, all of them vibrate, and we take these vibrations in, through the finely innervated skin surfaces of our toes and fingers, the plantar and palmar surfaces of our feet and hands, our legs, trunk, and back, through the proprioceptive stretch receptors of our ligaments, tendons, and fasciae, the baroreceptors of our arteries and veins, the gravity receptors of our inner ears, and, among the hearing, the specialized acoustic receptors of the cochlea. Sound is pervasive and inescapable, it is integral to how we experience the world and to how we ascribe value to different environments, it mediates our experience of stress and relaxation, fatigue and alertness, pain and pleasure. And yet, to date we have practically no language for talking about the justice or injustice of different kinds of acoustic environments, nor for talking about how different ways of experiencing sound shape and are shaped by power, inequality, and violence.