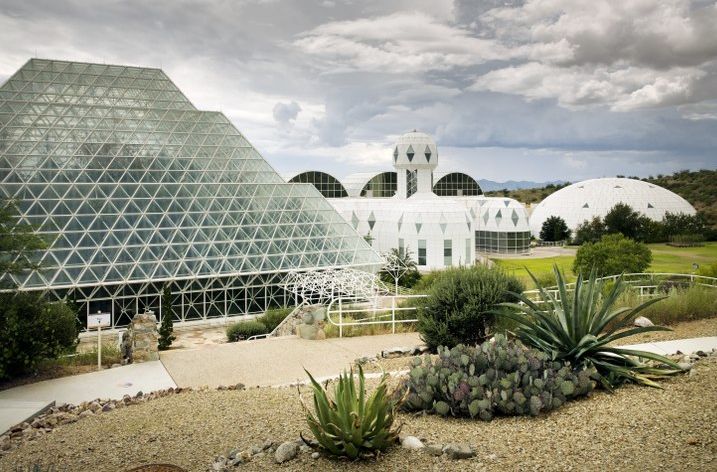

Carol M. Highsmith, 2008. Source: Library of Congress

Biosphere 2, Tucson, Arizona

Ecospheres: Model and Laboratory for Earth's Environment

The idea of a sealed habitable sphere has and continues to inform how life itself is understood. Tracing the historical roots of the miniature modeling of regenerative life systems and ecologies, historian of science Sabine Höhler encapsulates the varied technoscientific motives and consequences of experimenting with self-contained ecospheres and how they relate to the concept of life on Earth.

Life in a Bottle

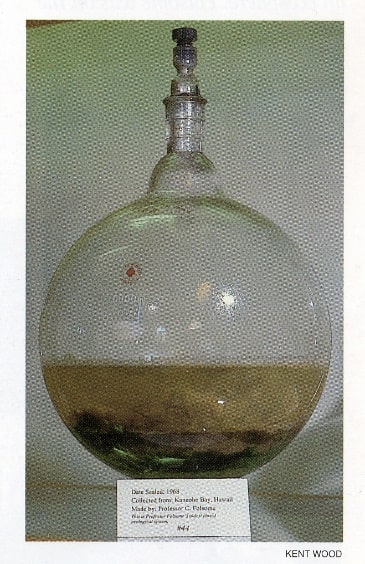

One day in the late 1960s a microbiologist by the name of Clair Folsome, professor at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu, went to the beach and scooped up seawater and sediment from the Pacific Ocean into a large glass jar. He sealed the jar tightly, left it sitting on a windowsill and nearly forgot about it, only to notice after days and weeks that the mixture of salt water and air, mineral and organic matter had not deceased but thrived. Folsome reasoned that the algae and microbes contained in the jar had been busy exchanging oxygen, carbon dioxide, and nutrients in a perfectly balanced and seemingly endless cycle. The bottled environment seemed to function as a small life-sustaining machine, powered by sunlight alone. The succession of material exchanges needed nothing else, as naught went to waste. As they fed on each other, the living creatures consumed, metabolized, and reproduced everything this wholly self-contained environment needed in order to survive as a whole. In his major work, The Origin of Life: A Warm Little Pond, in 1979, Folsome referred to enclosed ponds just like the one bathed in sunlight on his windowsill.Clair Edwin Folsome, The Origin of Life: A Warm Little Pond. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman and Company, 1979. He termed this self-sustained and stable tabletop microcosm the “ecosphere” (Figure 1).

Microcosm, Macrocosm

Miniature environments, tiny and yet encompassing such as the ecosphere, were well known in Folsome’s time. They had been studied not least in the form of the pond, a common social and ecological metaphor for the minimum viable habitat. The pond centered the village community and, since the late nineteenth century, it also represented the symbiotic community, or biocenosis, in emerging ecological thought.Frank Benjamin Golley, A History of the Ecosystem Concept in Ecology: More than the Sum of the Parts. London and New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993; Astrid E. Schwarz, Wasserwüste, Mikrokosmos, Ökosystem: Eine Geschichte der “Eroberung” des Wasserraumes. Freiburg: Rombach, 2003. Similar biotopes in the form of aquaria, vivaria, and terraria had arrived at zoological gardens and also in private homes around the turn of the twentieth century.Christina Wessely, “Wässrige Milieus. Ökologische Perspektiven in Meeresbiologie und Aquarienkunde um 1900,” Berichte zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte, vol. 36, no. 1 (2013), Special Issue: “Der Ozean im Glas: Aquaristische Räume um 1900”: pp. 128–47. An intriguing feature of these miniature environments was their glass technologies. Glass became crucial in the shaping of the notion of “environment” by way of carving out and separating segments of nature from their surrounding spaces.Kijan Malte Espahangizi, “Wissenschaft im Glas: Eine historische Ökologie moderner Laborforschung,” diss. ms., ETH Zurich, 2010. Transparent glass containers allowed human beings to both distance themselves from their objects of study and to observe environmental changes and continuities close-up and in real-time.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Folsome’s ecosphere was not perhaps a more fascinating, but certainly a more perplexing object of study than the common aquarium. The ecosphere set much stricter constraints on the living conditions inside. The glass container was completely sealed off from the outside world except for the energy it received from the sun, and yet its contents thrived. The ecosphere also proved more powerful as an epistemological tool. Despite being small, and because of being small, the closed system of the ecosphere could become a model for exploring questions about the principles of life, both in micro- and macro-scale communities. The ecosphere represented a totality in miniature, and this notion and the moving between scales of size it involved gave rise to new inquiries and imaginations.

The ecosphere represented the basic principles of life, minimally diverse and stripped to its simplest elements. Closely related to its minimalism was its self-containment. In the mixture of air and water, bacteria and algae were left to themselves in the sun “doing their ‘microbial thing,’” as the American systems ecologist John Allen would later phrase it.John Allen, Biosphere 2: The Human Experiment. New York: Penguin Books, 1991, p. 13. The glass sphere provided an ideal container to observe and to theorize the process. The spherical form expressed perfect symmetry, which in turn conveyed that matter and energy could circulate in an ideal, undisturbed, and frictionless fashion. This ecological conception of perfection also expressed a notion of the balance and harmony of earthly life through time.

These imaginaries of the ecosphere nourished a notion of life as an eternal force and process. Understood not as an individual but as a collective or ecological property, life generated and was engendered by endless loops of nearly self-identical reproduction. The ecosphere forwarded a notion of life as a self-driving and self-driven force that was anti-entropic—it counteracted the ever-increasing entropy which any energy transaction entailed. These imaginaries of the ecosphere were flanked by the new biogeochemical conceptualizations of life typical of that time in the 1960s. Now the life sciences understood life as autoactive and directed, yet wholly contingent, and in its self-organizing capacity able to overrule the second law of thermodynamics.The ongoing discussion in the natural sciences about what Life is can perhaps best be captured by Erwin Schrödinger’s renowned work What is Life?, from 1944, and the recurring references to that volume over the decades. Erwin Schrödinger, What is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell [1944], in What is Life?: With Mind and Matter and Autobiographical Sketches. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992; see, e.g., Addy Pross, What is Life? How Chemistry Becomes Biology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. Scaled to planetary size, the ecosphere allowed for an image and a model of the Earth itself as a spherical and wholly self-contained and self-sustained, timeless, and virtually perfect living environment.

Planet Earth, a Set of Spheres

By the time of Folsome’s experiments, the sphere already had a long history in the bio- and geosciences. Spheres were introduced to the Earth sciences in the nineteenth century as conceptual tools to describe and organize the organic and inorganic realms of the Earth in an ideal spatial form. The British geographer and natural philosopher Sir John Murray developed an expanded concept of “geospheres” in 1910, which would eventually also include the troposphere and stratosphere and form the basis of present-day geochemical and geophysical paradigms. Into the atmosphere—the sphere containing the thin shell of air surrounding the Earth’s surface—were nested, according to their extent, the hydrosphere, containing the ocean and freshwater bodies on the planet, and the lithosphere, the basic realm of soils and minerals forming the Earth’s crust.

The “biosphere” intersected with all of these concentric “envelopes of the earth.” The Austrian geologist Eduard Sueß had first defined the biosphere in 1875 as the sphere which encompassed all life on Earth.Eduard Sueß, Die Entstehung der Alpen. Vienna: Braunmüller, 1875, p. 158. Translations by Sabine Höhler. Sueß reflected on the “zone” on an Earth “formed by spheres” to which organic life was constricted; “on the surface of continents,” he asserted, “it is possible to single out a self-contained biosphere.”Ibid., p. 159. In 1926 the Russian mineralogist and biogeologist Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky published his main work The Biosphere. His project of a “physics of living matter” added a powerful basis on which to study cycles of energy and matter within the earthly environment. Formulating a unified biospheric theory, Vernadsky translated the “self-contained” biosphere of Sueß into a “self-maintained” biosphere.Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky, The Biosphere. Heidelberg and New York: Springer and Copernicus, 1998, pp. 15, 91 [revised and annotated English trans. of the original Russian version, Biosfera. Leningrad: Nauka, 1926].

In a paper of 1958 the American ecologist LaMont C. Cole termed the sum of all interdependent ecosystems of the Earth’s atmosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, and the surface layers of the lithosphere, the “ecosphere.”LaMont C. Cole, “The Ecosphere,” Scientific American, vol. 198, no. 4 (1958): pp. 83–92; LaMont C. Cole, “Man’s Ecosystem,” BioScience, vol. 16, no. 4 (1966): pp. 243–48. Cole’s ecosphere conceptualized planet Earth in its entirety as a materially closed and living ecological system powered by the Sun. This encompassing planetary ecosphere mapped directly onto Folsome’s bottled ecospheres; in turn, these offered both a model system and a laboratory to reflect on and experiment with the complexity and functionality of the Earth’s ecosphere in its entirety.

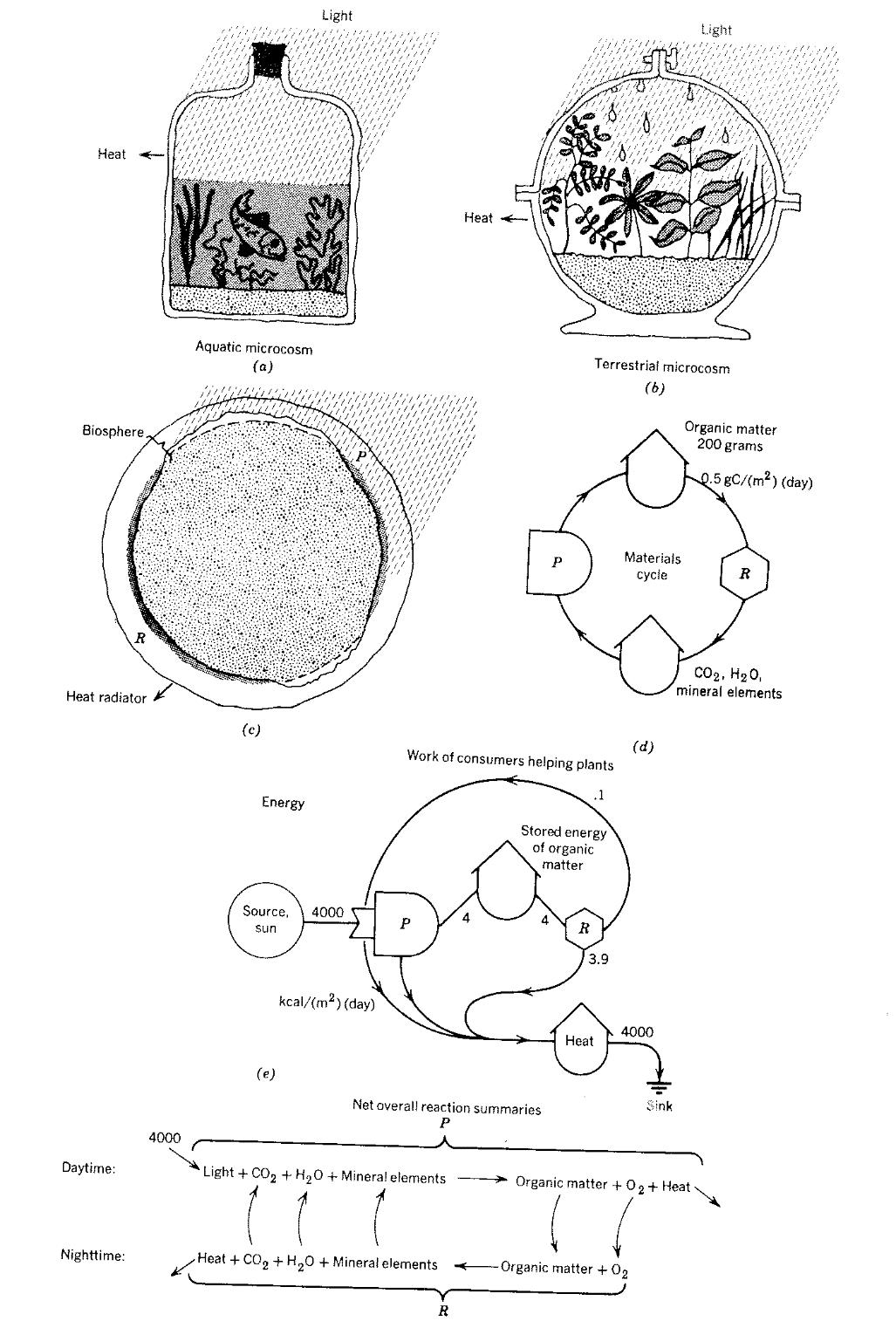

Howard T. Odum, American ecologist and a founding figure of ecosystem ecology, was one of several scientists who experimented with ecospheres as Earth analogs in the early 1970s, applying a strict ecosystem perspective and toolkit (Figure 2). Based on the studies of small living communities, Odum computed the daily power requirements for their “long-range survival” and sketched the production and consumption processes up to the planetary level.Howard T. Odum, Environment, Power, and Society. London and New York: Interscience-Wiley, 1971/1970, quote on p. 285.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

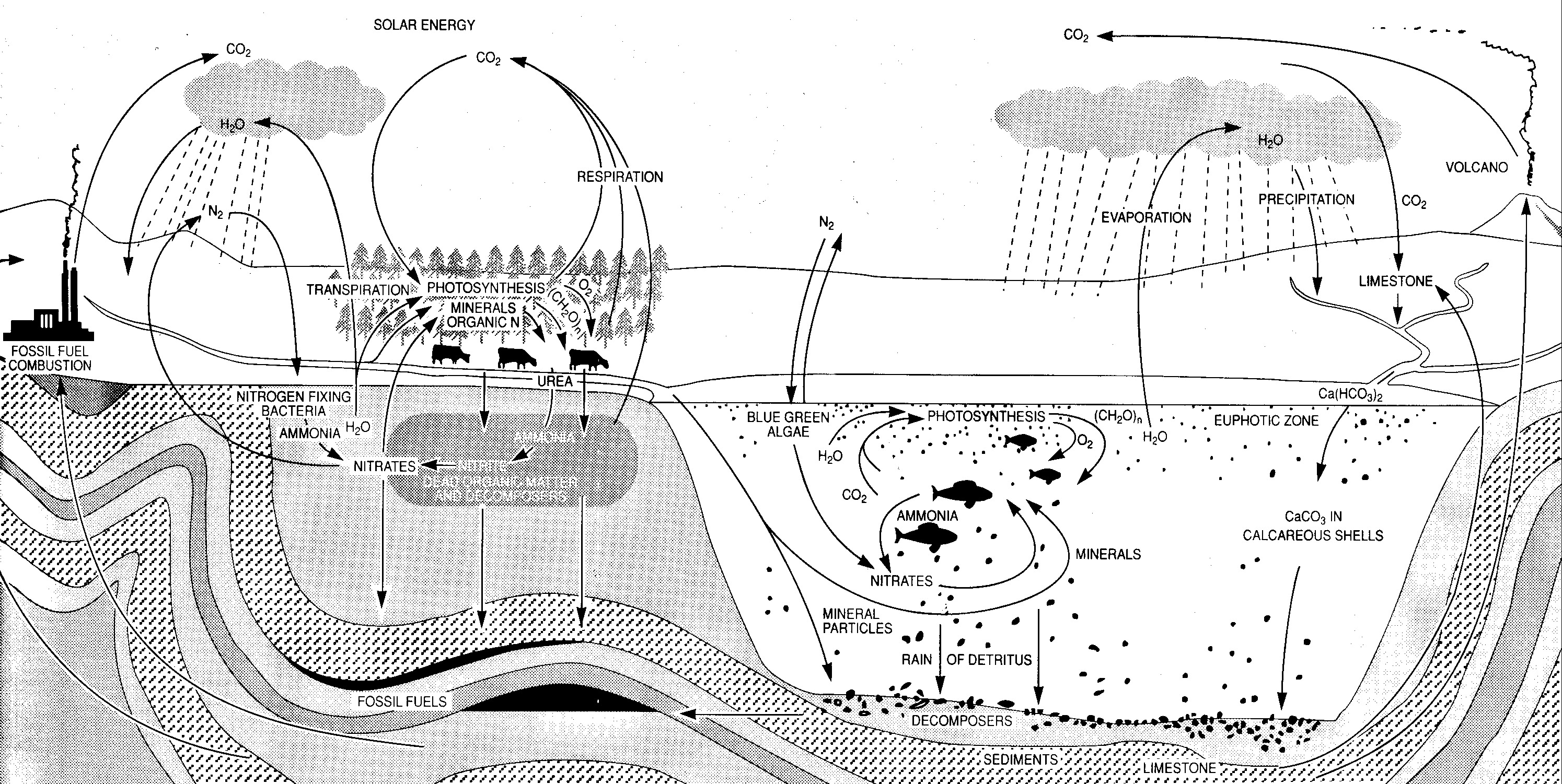

New to Odum’s and others’ ecological accounts of the time was that the processes of life in the Earth’s ecosphere did not seem to add up any longer to the stable balance sheets of the bottled ecospheres. As Odum saw it, the regenerative processes on Earth would be endangered, due to the “changing metabolic role of man.” As he termed it: “The biosphere with industrial man suddenly added is like a balanced aquarium into which large animals are introduced.”Ibid., pp. 16, 18. A similar picture of the Earth as a large ecosphere put off balance was applied by the American ecologist G. Evelyn Hutchinson. He understood the earthly biosphere as a closed circulatory system, which was fragile and far from perfect, whose boundary conditions limited the “amount of life” on the planet. In a highly regarded book of 1970, titled The Biosphere, Hutchinson based the “operation” and “day-to-day running” of the earthly biosphere on a systemic idea of managing an “overall reversible cycle” (Figure 3).G. Evelyn Hutchinson, “The Biosphere,” in The Biosphere. A Scientific American Book. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman and Company, 1970, pp. 3–11, quotes on pp. 8 and 5. As with Odum, Hutchinson’s biospheric system also included humans as an increasingly powerful biogeological entity and a force that was able to not only understand the workings of the biosphere but also affect it in irreversible ways.Ibid., p. 7. Hutchinson considered the development of utilizable fossil fuels within this cycle as an accidental and unfortunate imperfection that allowed vast fossil fuel-based human economies to upset the biospheric balance. This led Hutchinson to conclude with respect to the Earth’s expected lifespan: “It would seem not unlikely that we are approaching a crisis.”Ibid., p. 11.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The Endosphere

In scaling smoothly between micro- and macro levels, Folsome, Cole, Odum, and Hutchinson operationalized a principle of totality contained in miniaturized form, and vice versa, of microcosms fully enclosed in the entirety of the planet. This seamless play of scales was both a condition and an effect of an understanding of life’s structural order and functional complexity, information and energy exchange, and metabolic process and infinite reproduction. The early 1970s confirmed the conceptual shift from a phenomenological and spatial understanding of the terrestrial “envelopes” of the Earth, to which life was restricted, to a bio- and geochemical approach to both living matter and environments as self-regulating and evolving systems. At a time when the environmental effects of the postwar boom had become painfully noticeable in the Western world, systems ecologists sustained the hope that ecospheric models of life allowed for close environmental monitoring and, ultimately, planetary environmental management. Spheres, small and large, were constitutive for systems ecology to organize and model life’s energy cycles and material flows into idealized closed systems.

The German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk has reflected on such closed interior spaces, which he calls “endospheres.” His “ontology of enclosed space” proposes to understand the endosphere as an artificial container, created to offer dwelling for a selected population that faces a hostile or deteriorating outside world.Peter Sloterdijk, Sphären. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1998–2004, vol. 2: Globen (Makrosphärologie) (1999), chapter 3: “Archen. Zur Ontologie des ummauerten Raumes,” pp. 251 ff. Translations by Sabine Höhler. Such endospheres are highly exclusive encasements, Sloterdijk reminds us. Endospheric topologies include arks and similar insulated containers and vessels. The ecospheres discussed so far, both on the scales of Folsome’s bottles and of Cole’s planets, can be seen as endospheres in Sloterdijk’s sense. Ecospheres provided both self-containment and self-sustainment. The ecosphere of the Earth did indeed offer the only possible habitat for human life within the universe known at the time.

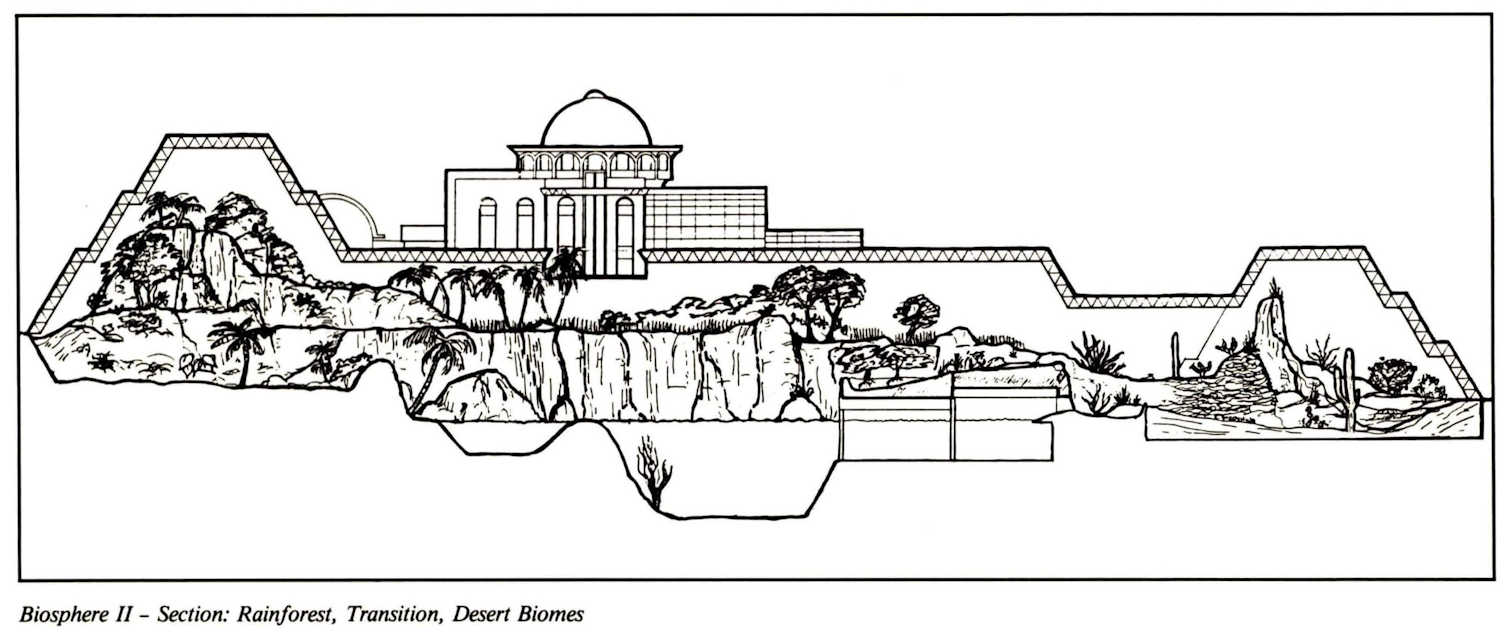

Sloterdijk’s ontology of enclosed space holds another interesting feature: it includes the radical idea of completely removing the endosphere from nature.Sloterdijk, Globen, p. 254. The project “Biosphere 2,” launched in the Arizona desert in the late 1980s, represented such an artificial construct of a nature materially isolated from the outside world. The aim of “Biosphere 2” was to facilitate the study of the ecological systems of “Biosphere 1,” the Earth, on the meso-scale. The goal was to develop a self-contained and ultimately self-sustained “living” system to secure “biospheric offspring” and evolve life beyond planet Earth.John Allen and Mark Nelson, Space Biospheres. Oracle, AZ: Synergetic Press, 1989, p. 33. Sabine Höhler, Spaceship Earth in the Environmental Age, 1960–1990. London: Pickering & Chatto 2015. “Biosphere 2” illustrates how biospheres and ecospheres modeled life as self-similar across scales. The principles of life’s self-regulation could be downscaled and put on trial. On a site of three acres, seven defined Earth ecosystems or biomes were created and then sealed under a glass dome. The “living laboratory” was populated by nearly 4,000 animal and plant species as well as eight human biospherians (Figure 4).

large

align-left

align-right

delete

To support the processes of life on the meso-scale, nature within “Biosphere 2” was based on a concealed technological infrastructure. The experiment called for the development of a new discipline called “ecotechnics,” which would interrelate the biosphere and the human-made “technosphere” in harmonious synergy.John Allen, Tango Parrish, and Mark Nelson, “The Institute of Ecotechnics: An Institute Devoted to Developing the Discipline of Relating Technosphere to Biosphere,” The Environmentalist, vol. 4, no. 3 (1984): pp. 205–18. Among a number of renowned systems ecologists the project managers engaged Clair Folsome, who was associated with NASA’s science program on closed ecological life-support systems and was the director of the laboratory of exobiology at the University of Hawaii. They closed the loop, so to speak. Folsome’s ecosphere stood at the beginning and at the end of experimentation with materially closed systems; it represented both environmental conservation on Earth and environmental expansion into space.Clair E. Folsome and Joe A. Hanson, “The Emergence of Materially Closed System Ecology,” in Nicholas Polunin (ed.), Ecosystem Theory and Application. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1986, pp. 269–88. David P. D. Munns and Kärin Nickelsen, “To Live among the Stars: Artificial Environments in the Early Space Age,” History and Technology (April 2018): pp. 272–99, doi: 10.1080/07341512.2018.1453911.

EcoSphere®

In a 1988 article titled “Ecosystems in Glass,” the American ecologist and agriculturalist Nicholas P. Yensen connected all the elements we have encountered so far, the bottled ecosphere, life under glass, and the Earth-like ecosystem of “Biosphere 2,” to take to Mars to create a sustainable human settlement. “Our future is in the hands of these crude homemade worlds,” Yensen claimed, “which potentially can give us the knowledge to go to the stars.”Nicholas P. Yensen, “Ecosystems in Glass,” Carolina Tips, vol. 51, no. 4 (1988): pp. 13–15, quote on p. 15.

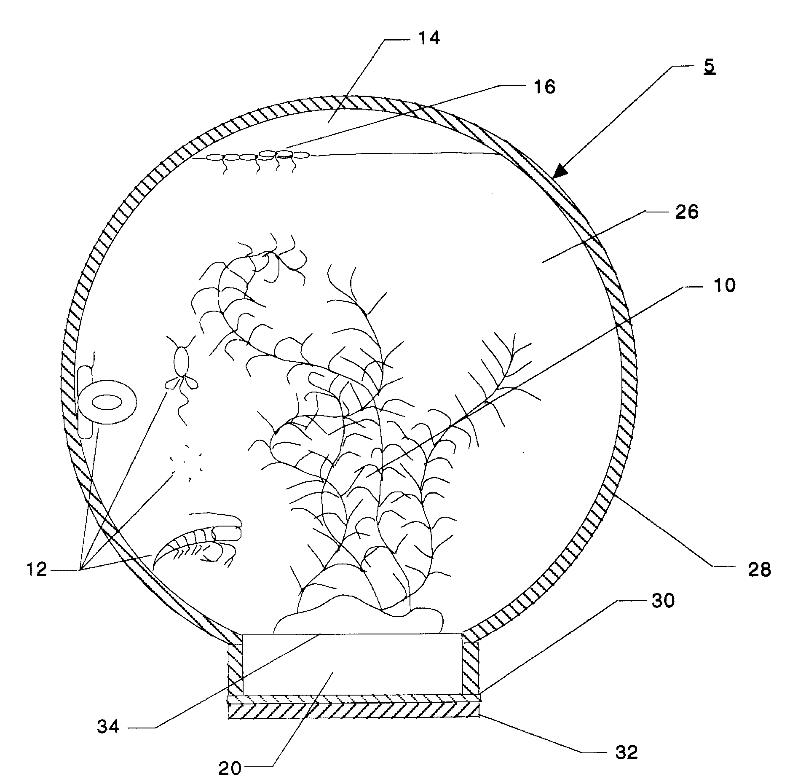

A new element also came into play, namely mass production and marketing. Yensen worked with Ecosphere Associates, Ltd, a company located in Tucson, Arizona, which researched closed ecosystems and which also commercialized them. Since the early 1980s and until the present, EcoSphere® branded a special mixture of micro-organisms, small shrimp, algae, bacteria, and filtered sea water, and marketed the mixture as “The world’s first totally enclosed ecosystem. A complete, self-contained and self-sustaining miniature world encased in glass.”EcoSphere® Closed Ecosystems [online](https://eco-sphere.com/); see also the cover story by Peter Warshall, “The Ecosphere: Introducing an Einsteinian Ecology,” Whole Earth Review, no. 46 (1985): pp. 28–31. The smallest EcoSphere® of ten centimeters in diameter costs around 80 US Dollars. Ecospheres are delivered with an instruction manual for care and maintenance, including a request to dutifully respect “occupants of the system as living beings.”

The mass production of ecospheres for a wider public might contribute to the implementation of an ethics of care, of minding the fragility of closed systems, small and large. “Our big world is very like this little one, and we are very like the shrimp,” so wrote the renowned American astroscientist Carl Sagan in his review of the tabletop “world#4210” that was shipped to his home in 1986.Carl Sagan “Review of the EcoSphere,” EcoSphere® Closed Ecosystems [online](https://eco-sphere.com/carl-sagan-review-of-the-ecosphere/). Cf. Carl Sagan, “The World that Came in the Mail,” in Billions and Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium. New York: Ballantine Books, 1997 [originally published in Parade magazine, 1986].

Amazon realized another corporate version of ecosphere architecture with its recent project “The Spheres,” inaugurated in their main office in Seattle on April 15, 2018. The Spheres are an urban office fashioned as a greenhouse, “home to more than 40,000 plants from the cloud forest regions of over 30 countries.” https://www.seattlespheres.com/ The commercialization of ecospheres certainly also created new cycles and value chains of technological reproduction by “using nature’s rules to build sustainable profits,” to quote Gregory Unruh and his book Earth, Inc.Gregory Unruh, Earth, Inc.: Using Nature’s Rules to Build Sustainable Profits. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2010. While both ethical and commercial aspects are worthwhile contemplating, a third aspect, articulated by Whole Earth Review and Wired editor Kevin Kelly, merits attention. In 1994, with reference to the experiment of “Biosphere 2,” Kelly commented that “life is a technology. Life is the ultimate technology.”Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1994, p. 165. On ecospheres and biospheres see chapter 8, “Closed Systems,” pp. 128–49.

The Technosphere

Kelly’s comment on life being a technology is perhaps best supported by looking at United States Patent no. 5,865,141, a patent for an ecospheric system, of 1999.U.S. Patent no. 5,865,141, “Stable and Reproducible Sealed Complex Ecosystems,” February 2, 1999. Inventors: Jane Poynter, Grant A. Anderson, and Taber MacCallum. Two of the three patent-holders, Jane Poynter and Taber MacCallum, belonged to the eight biospherians inserted into “Biosphere 2” during its first closure mission of 1991 to 1993. Their patented “Stable and Reproducible Sealed Complex Ecosystems” were down-scaled and analytically reduced versions of “Biosphere 2.” They were sealed, stable, reproducible, and ultimately also marketable technospheres, designed and patented as living systems. In the eyes of the inventors, these ecosystems far outperformed Folsome’s bottled ecosphere, because they contained and sustained higher life-forms (read: shrimps) (Figure 5). “The present invention allows much greater species richness and diversity, and allow all kingdoms of life to exist within a single, relatively small system.”Ibid., column 2.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

If there is anything to conclude at this point it might be that ecospheres have not deceased, they thrive, and that ecospheric cycles continue. Next to the cycle of life itself, it is the cycle of the technoscientization of life that thrives, the endless succession of scientific concepts and technologies to extract life’s regenerative mechanisms. The place and survival of human beings in the sealed complex ecosystems of ecospheres, however, remains a challenge. As Yensen remarked in 1988, “The actual placement of humans in truly closed systems for any significant duration has yet to happen anywhere on Earth, however, with the exception of the Earth itself.”Yensen, “Ecosystems in Glass,” p. 14.