Source: Wellcome Images

Ambroise Pare: prosthetics, mechanical hand.

The Alien Hand of the Technosphere. Kurt Goldstein and the Trauma of Intelligent Machines

Philosopher Matteo Pasquinelli investigates the curious history of the phantom limb syndrome and how it chronicles the confluence of war trauma research, neurology, cybernetics and the philosophy of mind. Is there a way by which all of that translates and extends to today’s planetary technosphere, being a prosthesis and a fear of amputation at the same time?

THE PARTIAL OBJECT OF TRAUMA

How to define trauma? Which models of trauma are unconsciously employed when we record the violence of man against man or the catastrophes triggered by the planetary technosphere against nature? How to explain the often traumatic event of the social implantation of new technologies? Is there an Object, maybe a technical Object, which may illuminate our idea of trauma and its psychic structure, rather than narrating one of its historical incidents? Can trauma really be represented by a concrete object, or rather always indicated by a broken object, an amputated body, an invisible wound, a missing dear friend, an abstract process in absentia? More importantly, will we ever be able to see trauma beyond the ideas of lack, amputation, and victimization, and to frame it as positive and pre-emptive endeavor? We could start from these questions and wonder to what degree psychic and technological traumas are a healing process, whose nature is that of being a fragment of a failed unity and the figure of a complex assemblage yet to be.

The present contribution attempts to illuminate the (symbolic) form of trauma by looking at German neurology in the Weimar era, as studies on brain traumas around the time of the First World War happened to influence the development of cybernetics and machine intelligence after the Second World War. In fact, at the beginning of cybernetics a notion of trauma was not at all alien to the design of intelligent machines, and this lineage of thought had a surprising influence on French philosophy as well. Rediscovering the genealogies of trauma across twentieth-century neurology, cybernetics, and philosophy hopefully will be of benefit to the debate on the technosphere of the Anthropocene.

THE PHANTOM LIMB

One vivid way to objectify trauma in the field of neurology is to consider the accident of an amputated limb and to study the emotional and cognitive consequences of such an amputation, as in the famous phantom limb syndrome. Phantom limb syndrome is a neurological condition in which the presence of a hand, arm, or leg is still perceived to exist even after amputation, with the amputee suffering pain associated with the limb as if it were not missing. Phantom limb syndrome is a clear example of the deep and unresolved tension (for both philosophy and neurology) between the modern categories of body and mind. The artist Alexa Wright has worked with neurologists and patients to reconstruct, in fictional photographs, the exact spatial position in which amputees perceive their phantom limbs (suggesting that physical traumas are, in the end, always of a cognitive nature).

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The neuroscientist Vilayanur Ramachandran famously conceived a simple therapy to cure the pain of phantom limb syndrome: the mirror box.Vilayanur Ramachandran and Sandra Blakeslee, Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the mysteries of the human mind. New York: William Morrow, 1998. The image of the right hand in a mirror that is perpendicular to the torso can produce, for instance, the illusion of the presence of an amputated left hand.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

"The box is made by placing a vertical mirror inside a cardboard box with the roof of the box removed. The front of the box has two holes in it, through which the patient inserts his good arm and his phantom arm. The patient is then asked to view the reflection of his normal hand in the mirror, thus creating the illusion of two hands, when in fact [he] is only seeing the mirror reflection of the intact hand. If he now sends motor commands to both arms to make mirror-symmetric movements, he will have the illusion of seeing his phantom hand resurrected and obeying his commands, i.e. he receives positive visual feedback informing his brain that his phantom arm is moving correctly."Vilayanur Ramachandran and William Hirstein, “The perception of phantom limbs,” Brain 121, no. 9 (1998): 1620.

Such a machination can fool the brain’s perception of the body: it intervenes at the level of the body schema that is projected by vision, and it constructs a temporary cognitive map of the amputated hand and thus alleviates the neurological distress.

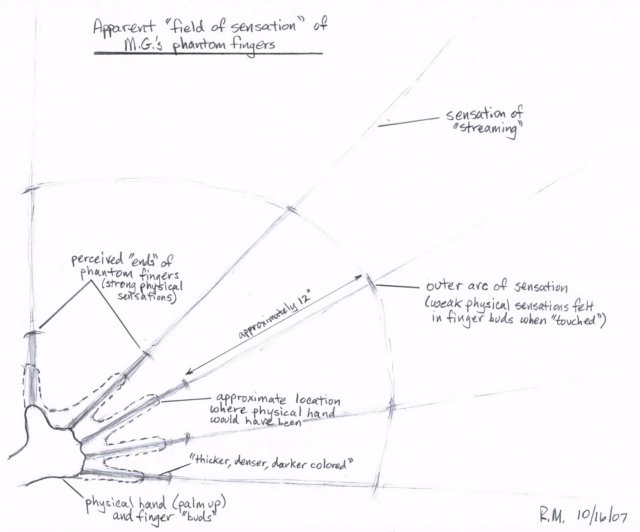

Phantom limbs may hold abnormal dimensions. Robert and Suzanne Mays made a drawing of the apparent “field of sensation” around the physical left hand of a patient known as MG; in the body schema of this patient, the fingers extended far outside the space of the hand that had been amputated. Phantom limbs that grow out of proportion are called “mind limbs,” as the brain projects a cognitive map beyond the coordinates of the previous body schema. If the projection of this hand looks abnormal, it is nevertheless the projection of a form of life trying to occupy the surrounding void and fight for its place in the surrounding environment. The brain attempts desperately to cast off its old body image, but something slips off and falls into the infinite.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

THE ALIEN HAND, OR THE HAND THAT THINKS

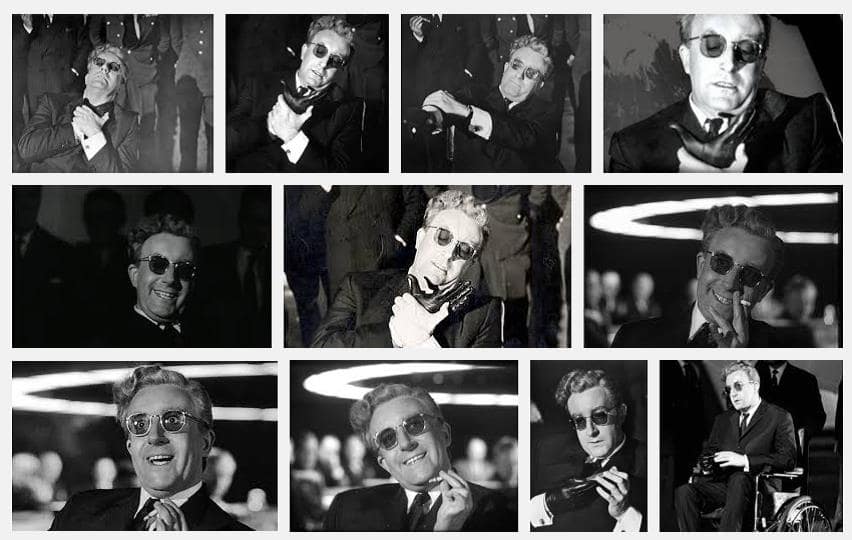

More uncanny still in the cabinet of neurological traumas is the syndrome known as the alien hand, which was first described by the German-Jewish neurologist Kurt Goldstein in 1908.Kurt Goldstein, “Zur Lehre von der motorischen Apraxie” [On the doctrine of the motor apraxia], Journal für Psychologie und Neurologie 11, nos 4/5 (1908): 169‒87. In this syndrome, after a brain injury, or in the case of diseases like Alzheimer’s, one hand starts to move autonomously like it has a will of its own. In the first clinical case registered by Goldstein, the alien hand was trying to strangle a fifty-seven-year-old woman while she slept. In another instance, the right hand was buttoning up a shirt, while the left hand happened to unbutton it at the same time. A famous cinematographic reference of such a syndrome is seen in Stanley Kubrick’s movie Dr. Strangelove in which a megalomaniac American scientist is fighting against the Nazi drives of his own hand (clearly a reference to the Nazi military that was passed to the United States after the end of the Second World War).

small

align-left

align-right

delete

Patients often describe this phenomenon as having their hand possessed by a demon or a spirit.Alien hand syndrome should not be confused with anarchic hand syndrome, where in the latter the hand moves independently but is still recognized as part of the body. See Thomas Metzinger, Being No One: The Self-Model Theory of subjectivity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003, p. 424. In comparison to the phantom limb, this is a different and complementary case: if phantom limb syndrome is about the virtual projection of an absent limb, alien hand syndrome is where an existing hand is no longer perceived as part of the body and acquires a will of its own. Whereas in the case of the phantom limb the body has lost one component yet the brain keeps on projecting the same body schema, in the alien hand case the body remains undivided, yet the body schema seems to be divided into two parts. Interestingly for both neurologists and patients, the alien hand appears to have developed a “mind of its own.”

As the American neurologist Norman Geschwind acknowledges, Goldstein was perhaps the first to stress “the nonentity of personality” in patients with trauma of the corpus callosum, the conurbation of nerves connecting the right- and left brain hemispheres.Norman Geschwind, Selected Papers on Language and the Brain. Boston: Reidel, 1974, p. 225. Goldstein is renowned for having developed a holistic theory of the brain, but with the alien hand case he showed that our mind is separable in autonomous circuitries—circuitries that appear to reorganize themselves after a trauma and provoke not just cognitive dissonance, but the split of cognition itself. Goldstein’s description of the alien hand was one of the first accounts (together with English neurologist Henry Head)Stefanos Geroulanos and Todd Meyers, “Integrations, Vigilance, Catastrophe: The neuropsychiatry of aphasia in Henry Head and Kurt Goldstein,” in David Bates and Nima Bassiri (eds), Plasticity and Pathology: On the formation of the neural subject. New York: Fordham University Press, 2015. to recognize that the brain produces a map of the body that is continuously and unconsciously readjusted: a theory neurophilosopher Thomas Metzinger recently expanded upon with his idea of the Phenomenal Self-Model.See Thomas Metzinger, The Ego Tunnel: The science of the mind and the myth of the self. New York: Basic Books, 2009.

Goldstein is a forgotten influential figure of Weimar-era Berlin: he left as crucial a mark on French philosophy as he did on American cybernetics thanks to his sophisticated idea of brain trauma and cognitive catastrophe. Before clarifying this, it is worth remembering his biography. Born in Katowice, Poland (and cousin of philosopher Ernst Cassirer with whom he maintained close relations all his life), Goldstein became the head of the neurology department at Berlin Moabit hospital after studying the brain injuries of Second World War soldiers in Frankfurt. Being of Jewish lineage and also a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), Goldstein was arrested and tortured by the Nazis in 1933 and released only after the intervention of a psychoanalyst who was in contact with Hermann Göring; yet attached to his freedom was the strict order to leave Germany forever. In 1934, in Amsterdam, he dictated his seminal book Der Aufbau des Organismus “almost nonstop, over a period of five weeks, leaving himself (and his typist) in a state of prostration,” as Oliver Sacks reminds us in his introduction to the English edition of the book.Kurt Goldstein, Der Aufbau des Organismus. Einführung in die Biologie unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Erfahrungen am kranken Menschen. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1934; published in English, The Organism: A holistic approach to biology derived from pathological data in man. Salt Lack City, UT: American Book Company, 1939; New York: Zone Books, 1995. In 1935, supported by the Rockefeller Foundation, Goldstein arrived in New York where he died in September 1965, after working in prominent universities such as Columbia and Harvard and also teaching at the New School. Der Aufbau des Organismus was not a work of philosophy, but it is probably the neurology text that has had the greatest impact on the philosophy and technology of the twentieth century. As Anne Harrington stated once, the story of Goldstein was a true Weimar story, something to rediscover a long century after his birth and exactly fifty years after his death in New York.Anne Harrington, Reenchanted Science: Holism in German culture from Wilhelm II to Hitler. Princeton University Press, 1999.

KURT GOLDSTEIN AND THE CATASTROPHIC BRAIN

Why rediscover Goldstein’s work on brain trauma, shock, and catastrophic reactions? Goldstein introduced a proactive definition of these notions rather than a passive one. For Goldstein the brain is constantly in a state of active shock and even arranges “slight catastrophic reactions” in the act of coming to terms with the world.Goldstein, The Organism, p. 227. It is worth noting that in the same years, around 1920, Sigmund Freud was developing the theory of the death drive, in which a biological primacy is granted to inorganic matter, and trauma is defined negatively as the inability to restore a previous state.Sigmund Freud, Jenseits des Lustprinzips. Leipzig, Vienna, Zurich: Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag, 1920. Goldstein was influenced by the holistic tradition of the German Naturphilosophie (the “philosophy of nature,” rather than hard sciences like Freud), nevertheless he expanded on Immanuel Kant’s notion of organic unity, and recognized the abnormal and pathological state as the modus operandi of the mind.

For Goldstein, both normal and abnormal behaviors are the result of the brain’s antagonism with the environment: abnormal states of mind are an expression of adaptation as much as the normal states are.Goldstein was contemporary with German Expressionism and it would not be too surreal to record its echoes throughout the Berlin circles of neurology. Symptoms of illness are not secondary effects, but a sign of a positive endeavor toward a new condition, a sign that the organism is struggling to find a new equilibrium. The truly sick organism, according to Goldstein, is that which doesn’t deviate from the norm, the one that cannot invent new norms. The organism that never falls sick is the truly sick one. This intuition will have a profound influence on French philosophy, on the way, for instance, Georges Canguilhem and Michel Foucault will define the abnormal. Many forget that Foucault opens his first book Maladie mentale et personnalité with a critique of Goldstein.Michel Foucault, Maladie mentale et personnalité. Paris: PUF, 1954. And Canguilhem himself echoes Goldstein in his famous statement: “The abnormal, while logically second, is existentially first.”Georges Canguilhem, The Normal and the Pathological, with an Introduction by Michel Foucault. New York: Zone Books, 2007, p. 243.

Furthermore, Goldstein established and investigated the link between abnormality and abstraction. Antagonism with the environment, the struggle for adaptation, always proceeds by the invention of new equilibria, habits, norms, and categories. Adaptation always happens via the production of new abstractions. How does trauma affect the ability to produce new abstractions? Goldstein offers the example of one of his patients who refuses to repeat a false sentence such as “the snow is black.” The patient could agree to repeat each single word but the not the whole sentence; he would only agree to repeat the correct sentence “the snow is white.”Kurt Goldstein, Human Nature in the Light of Psychopathology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1940, p. 55. This behavior was not the refusal to lie, but the inability to suspend the rules of common sense just for a moment, as sense of humor, speculation, or linguistic exercises may require. In this case the brain trauma provokes the incapacity to abstract from the concrete behavior of the everyday. Indeed, a clear symptom of trauma for Goldstein was not necessarily disordered behavior, but for instance, an excessive attention to order. Goldstein noticed that a few postwar soldiers with severe brain injuries were keeping their hospital rooms perfectly in order. Everyday, they were cleaning and sorting the things in their room in a maniacal way. A sudden change in the disposition of objects, or the event of an unexpected visitor, could provoke discomfort and panic. These patients could not tolerate the minimum degree of disorder in their Umwelt, their surroundings, in which case order was a symptom of trauma. Goldstein thought that spatial order was not a necessary condition of an adaptive brain: the disposition and function of objects can be mentally manipulated independently by their physical disposition. He believed that brain trauma may affect the brain’s power of abstraction, that is, the ability to recognize complex shapes in unusual contexts and the ability to live within a space of chaotic disposition of objects and people.

In general, the power of abstraction for Goldstein is the power “to plan something in the future,” “to construct hierarchies of value,” “to perform symbolically,” “to detach our ego from the outer world or inner experience.”Kurt Goldstein and Martin Scheerer, “Abstract and concrete behavior an experimental study with special tests,” Psychological monographs 53, no. 2 (1941). The power of abstraction is the power to alienate from the ground of nature itself. The work of his cousin Ernst Cassirer would push Goldstein to translate his conclusions to the social and cultural sphere. Symbolic forms in general, such as education, art, and science are necessary “to come to terms with the world.”Goldstein, Human Nature, p. 244. For Goldstein, the brain is in a continuous process of self-actualisation, and after a (psychic or physical) trauma it keeps on inventing new norms and behaviors in a multitude of unexpected ways. Goldstein’s model is helpful to clarify both the phantom hand and alien hand syndromes, but the manual of neurology should expand their taxonomies to also include the new syndromes of cognition in the age of intelligent machines.

ATOMIC TRAUMAS AND THE BIRTH OF CYBERPHILOSOPHY

The emergence of the digital computer was also the consequence of a war trauma, this time the shockwave of the first nuclear experiments during the Second World War. The magnitude of the mathematical operations required to calculate and control the out-of-scale detonation of the atomic bomb pushed forward development of the first mainframe computers at the Princeton Institute for Advanced Studies.George Dyson. Turing's Cathedral: The Origins of the Digital Universe. New York: Vintage, 2012. The Big Bang of the Turing universe ran along Albert Einstein’s equation of matter and energy, which was behind the measurement of the potential of nuclear binding in the radioactive kernel. Cybernetics was sponsored by generous grants from the US Defense Department, but as the science historian Andrew Pickering has shown, early cybernetics, in fact, was more deeply influenced by biology and neurology than by information theory.Andrew Pickering. The Cybernetic Brain: Sketches of Another Future. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 2010. We should not forget that Norbert Wiener dedicated a chapter of his 1948 classic to “Cybernetics and Psychopathology” and discussing memory loss as the root of neurosis, Wiener states that: “Pathological processes of a somewhat similar nature are not unknown in the case of mechanical or electrical computing machines.”Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics: Or, Communication and Control in the Animal and Machine. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1948, p. 172.

The epistemologist David Bates has traced back the role of error, abnormality, and catastrophe in the design of the early cybernetic systems following the influence of Goldstein. Bates traces Goldstein’s idea of “slight catastrophic reactions” to demonstrate that many theorists of the cybernetic era were interested in machines as well, which could show properties of self-repair after a catastrophic or traumatic accident.David Bates, “Unity, Plasticity, Catastrophe: Order and Pathology in the Cybernetic Era,” in: Catastrophe: History and Theory of an Operative Concept, eds. Andreas Killen and Nitzan Lebovic. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2014. This early stage of cybernetics is often forgotten, but it is curious how the paradigms of “brain damage” and “self-repair” are emerging once again in recent developments of machine intelligence. Neural networks are in fact machines that learn by error and sometimes networks are intentionally designed to fail in order to learn and adapt. Machine intelligence research has acquired, for instance, the idea of optimal brain damage (also known as “pruning”), which is a trick to improve the computational power of neural networks by weakening the strength and number of connections, rather than multiplying them, as one might expect.Yann LeCun, John S. Denker, and Sara A. Solla, “Optimal brain damage,” Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS) 2 (1989).

The idea of neural networks and the whole business of machine learning run by error, by breaking up, is a strange nemesis for Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s idea of desiring machines, machines of the productive unconscious “that continually break down as they run, and in fact run only when they are not functioning properly,” as the famous quote goes.Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, vol. 1. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1983, p. 34. Deleuze and Guattari’s idea was also a reference to Canguilhem’s 1947 lecture “Machine and organism,”Georges Canguilhem, “Machine and Organism” (lecture given in 1947), in Paola Marrati and Todd Meyers (eds), Knowledge of Life: Georges Canguilhem. New York: Fordham University, 2008. which may have also inspired Donna Haraway’s figure of the cyborg during her period in Paris.Ian Hacking, “Canguilhem amid the cyborgs,” Economy and Society 27, nos 2/3 (1998): 202‒16. The parallel evolution of French philosophy and Anglo-American cybernetics is particularly striking: with French philosophy devoted to the history and liberation of madness, mental illness, sexual abnormality, and schizophrenia, and Anglo-American cybernetics obsessed with intelligent machines and the mechanization of the mind.Matteo Pasquinelli, “Abnormal Encephalization in the Age of Machine Learning,” e-flux 75 (September 2016). Looking attentively, the two lineages share a common root in the positive definition of cognitive trauma and catastrophic reaction that has since been forgotten.

In 1955 the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan dedicated one of his seminars to cybernetics and the new calculating machines.Jacques Lacan, “Psychoanalysis and cybernetics, or on the nature of language.” The seminar of Jacques Lacan. Book 2. Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller. Cambridge University Press, 1988. Lacan positively registered the new regime of cybernetics as a further stage in the decentralization of the human subject.See: Céline Lafontaine, “The Cybernetic Matrix of French Theory”, Theory Culture Society 2007, 27-46. The German media scholar Friedrich Kittler has stressed the influence of cybernetics on Lacan and French thought, specifically on their new account of subjectivity that would be influenced, according to Kittler, by new acephalous machines that were able, for the first time, to talk and think automatically.Friedrich Kittler, “The World of the Symbolic—A World of the Machine,” in Literature, Media, Information Systems. Amsterdam: G+B Arts International, 1997. The history of early cybernetics shows how much of the original definition of brain trauma and abnormality has been absorbed, reinforcing the supremacy of the paradigm of machine intelligence against other epistemologies. Yet the old question of French post-structuralism is still relevant, and today it can be reformulated as follows: What are the rights of the abnormal mind in the age of Artificial Intelligence and its corporate dreams?

TECHNOLOGICAL PHANTOM LIMBS

The clumsy imbrication of res cogitans and res extensa that has haunted modern philosophers continues in the age of machine intelligence under unexpected metamorphoses. Biomechatronics has conceived, for instance, a new generation of prostheses that are installed thanks to a dynamic socket that maps nerve and muscle movements in the amputee’s body. The prototypes of biophysicist Hugh Herr at MIT Media Lab show that patients can begin walking with these artificial limbs without training.See the website of MIT Media Lab (http://biomech.media.mit.edu), accessed October 22, 2016. A new “cognitive map” of body movements is produced by machine-learning algorithms which operate the artificial limbs in real time as a sort of external motor cortex, matching human and machinic body schemata. These prostheses are extensions of the body as much as of the mind, as the latter has to dock a newly extended body with computational ability. As known, artificial limbs can outperform the strength of natural ones, and in doing so they establish new norms for human nature.

Conversely, Virtual Reality and new immersive technologies are being used to treat psychic and physical trauma. Ramachandran’s mirror box illusion, used in the treatment of phantom limb pain, can now be expanded with a VR headset through which the amputee sees the missing arm movements in a very realistic way. Also, as documented by filmmaker Harun Farocki in his installation Serious Games (2009), 3D simulations of war scenarios are used in the therapeutic treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, in which the patient repeatedly enacts the very moment of the traumatic event. Immersive technologies further explore the imbrication of digital simulations with body schemata, and can be used to warp body perception for non-medical purposes as well.

Given a new technosphere of cognitive and physical prostheses, new types of phantom limb and alien hand syndromes can be recognized (and the failure or success of their cognitive imbrication can illuminate the rise of new abnormal minds). Technological phantom limb could be described as media prosthesis that leave a disoriented and fragmented cognitive map once they disappear. Everybody is familiar with this type of disorientation and distress: it happens anytime we are cut off from technological extensions such as mobile phones, email, and social media. Consider the reaction of the brain to that disorientation and the way the brain tries to “rewire” differently with the environment.

On the other hand, technological alien hands may be robotic structures, intelligent systems, and large infrastructures that appear to behave on their own against human will, after a major failure of extended cognition. We already live in a world in which independent intelligent infrastructures make decisions by themselves or on behalf of humans (what the French philosopher Bruno Latour calls actants).Algorithmic agency is already producing new legal problems for corporations and military institutions. See Susan Schuppli, “Deadly Algorithms: Can legal codes hold software accountable for code that kills?”, Radical Philosophy 187 (2014): 1‒8. The 2010 Flash Crash of the US stock markets, provoked by out-of-control High Frequency Trading algorithms, is a good example of endogenous catastrophe in the age of machine intelligence. The thought experiment of imagining the amputation of large parts of the technosphere and the disruption of the computation power that control society maintained was proposed for the first time a long time ago. In his 1948 classic Cybernetics, Wiener already asked if it were really conceivable to stop the domain of cybernetic machines without a catastrophic effect on society. Today, what is the degree of autonomy of humankind against megamachines of computation such as Google, for instance?

CATASTROPHE THEORY WITHOUT CATASTROPHISM

Goldstein had the intuition to reverse the relationship between trauma and cognition: his work seems to suggest that we should consider trauma as the modus operandi of cognition in general, rather than see cognition as a way to elaborate and overcome specific traumas. The idea that the human brain simulates and self-organizes small cognitive catastrophes could be extended, metaphorically, to the global brain of the technosphere. The computing apparatuses of the technosphere (what others would call the infosphere or, after Vladimir Vernadsky, the noosphere) are perhaps just another extension of our pre-traumatic adaptors or, more precisely, of our pro-traumatic predictors, that simulate potential catastrophes in order to solve planetary troubles. Considering also the scale of its framework, the Anthropocene paradigm is possibly one of these pro-traumatic predictors. Consistently, catastrophism is defined as the paranoid and monotonic repetition of the cognitive faculty of catastrophe simulation, indeed as the problem of seeing a catastrophe where there is none.

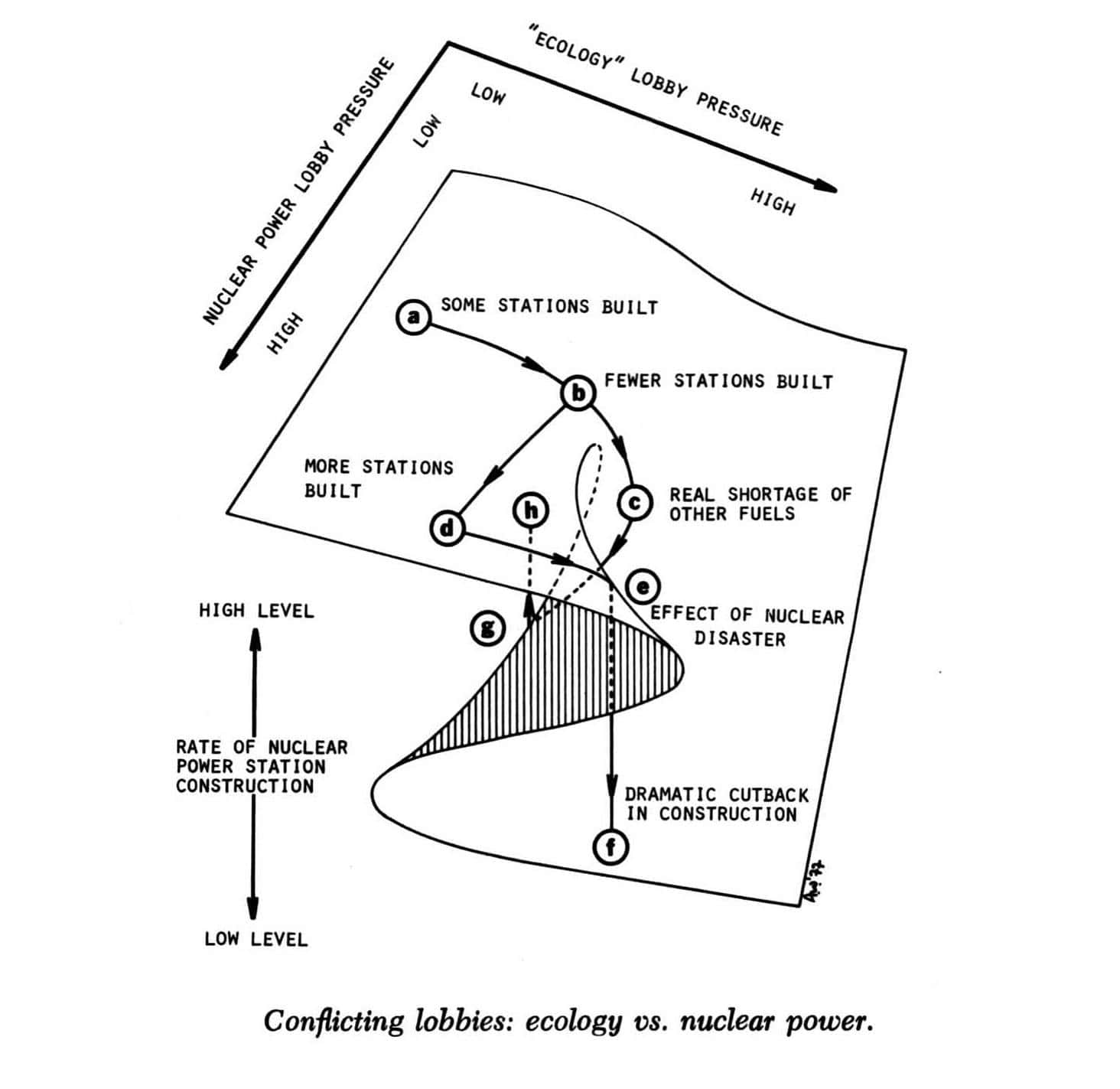

A question by way of a conclusion: do we possess a robust paradigm of trauma at the same level and scale as planetary computation? After his introductory speech for the 2014 Anthropocene Campus at the HKW, historian of science Jürgen Renn reminded the audience that even if nuclear power were discontinued as a source of energy, the knowledge around nuclear power and infrastructure had to be maintained and cultivated. Nuclear power is a fitting case study to compare and assess trauma studies and catastrophe theories. The 1978 book Catastrophe Theory offers a diagram (inspired by the work on topology by the French mathematician René Thom) that attempts to describe the unfolding of a political crisis in relation to nuclear power.Alexander E. R. Woodcock and Monte Davis, Catastrophe Theory. New York: Dutton, 1978.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Thom admitted that his research on the topology of catastrophe was actually inspired by Goldstein’s idea of the catastrophic reaction of the brain, which he wanted to expand outside the domain of the psyche. Thom’s model aimed to describe biological morphogenesis, like the growth of a cell or a plant, but in fact it is very close to a description of a dynamic form of trauma. The idea behind catastrophe theory and its application to different scales and domains seems to also be an attempt to elaborate an expanded body schema for the planetary technosphere. What is common to both Goldstein and Thom is faith in the invention of higher forms of knowledge and abstraction, through which it could be possible to regain control of the technosphere when it runs out of control—and before it may strangle us like an alien hand.

The author would like to thank Nina Franz for her comments.