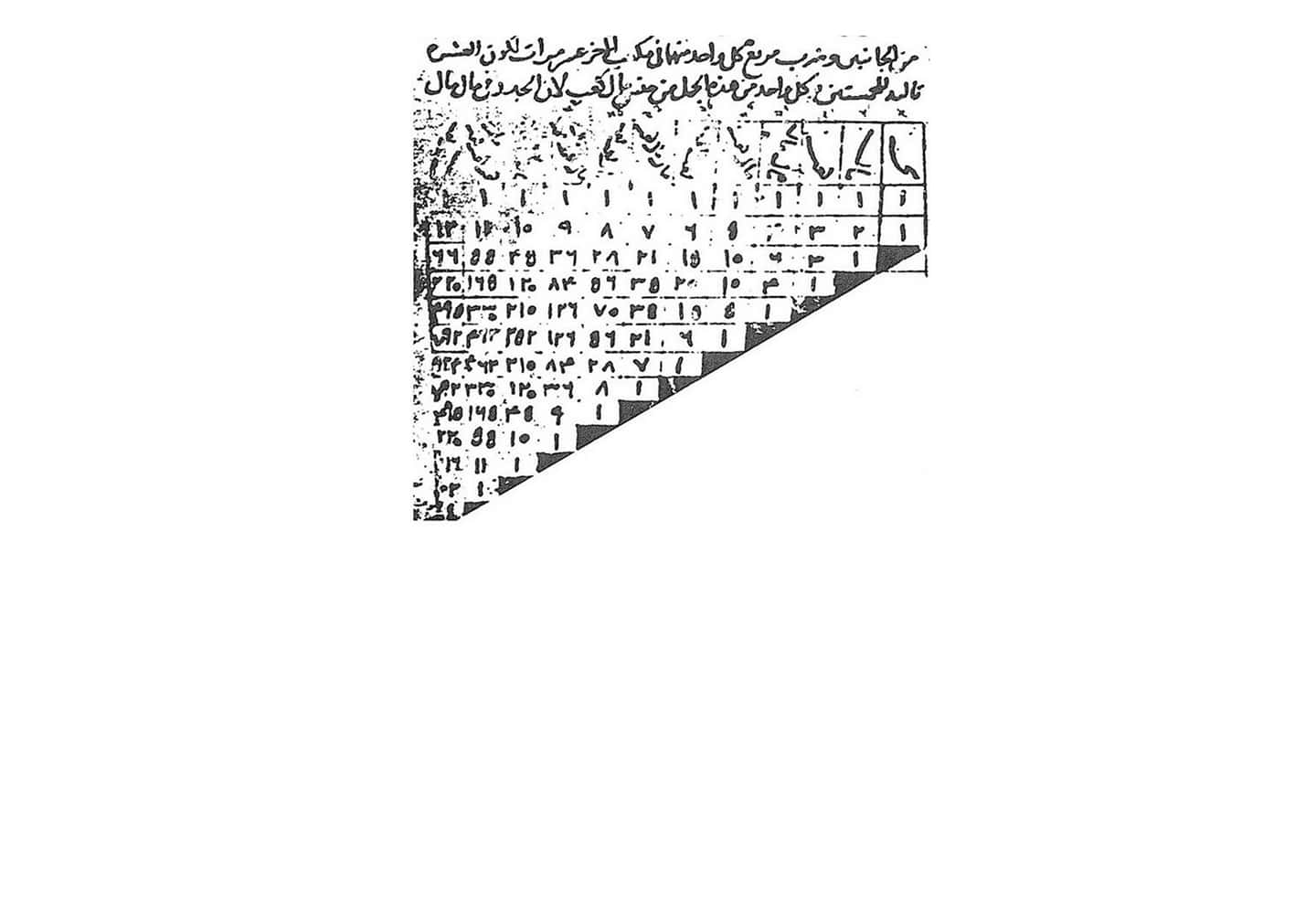

Al-Karaji, Inductive Proof of the Binomial Theorem (c. 953 – c. 1029)

The Inclosure of Reason

Tracing thoughts on the inhuman found in ancient Hindu and Buddhist texts up through recent functionalist theories of mind, artist and theorist Anil Bawa-Cavia calls for a new, diagonalized notion of reason distinct from that of logos still employed by humans. Using logic and experiments in game-playing neural networks, he exposes a Copernican humiliation—or Turing trauma—that sees the human as only one situated embodiment of reason and not its apex.

To produce, in the world such as it is, new forms to shelter the pride of the inhuman – that is what justifies us.

—Alain BadiouAlain Badiou, Logic of Worlds. London and New York: Continuum, 2009, p. 8.

Expanding the ambit of humanism beyond the dominant Western account is a first step in estranging humanism from itself, in recasting the human as an agent of that vector of reason we call intelligence. One might begin in the Vedic period (1500–900 BC), in the “Nasadiya Sukta,” the 129th hymn of the 10th mandala of the Rig Veda, the earliest of the four major Vedic texts. This creation hymn, whose name derives from ná ásat, or “not the non-existent,” opens with the paradox of creation:

नासदासीन्नो सदासीत्तदानीं नासीद्रजो नो व्योमा परो यत्

Translated as “not the non-existent existed, nor did the existent exist then":Anonymous, trans. Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty, “Nasadiya Sukta,” Rig Veda (10:129). Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics, 1981. the hymn negotiates the limit of creation with one of the earliest recorded instances of agnosticism – that precondition for a human reason unburdened by theological imperative, and the earliest flicker of a nascent humanism:

Who really knows? Who will here proclaim it? Whence was it produced? Whence is this creation? The gods came afterwards, with the creation of this universe. Who then knows whence it has arisen?Anonymous, trans O’Flaherty, “Nasadiya Sukta,” Rig Veda (10:129).

It is precisely this agnostic attitude at the root of humanism, itself a regard for the limits of human reason, which needs to be reoriented in the direction of those forms of artificial intelligence (AI) developing today. An attitude that compels modesty in its open admission that the inhuman may elude our epistemological framing of intelligence itself.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Likewise, one might render a history of inhumanism through a figure like Nāgārjuna, the first-century Buddhist thinker who asserted that all existence is necessarily without essence. Nāgārjuna adopted the Nyāya school of Indian philosophy, with its multi-valued, non-binary logic, to enact a “middle way” in thought that sought not to resolve ontological contradictions but rather counter propositions through a fourfold negation (catuskoti). One can trace inhumanism from this radically non-essentialist view of the human, to Bhāskara II, the medieval Indian mathematician whose invention of the chakravala,The word chakra translates to “cycle.” a cyclic algorithm developed to solve quadratic equations, was the first sophisticated iterative method—the enunciation of a hitherto unknown recursive logic. The procedure bore some relation to Al-Karaji’s proof by mathematical induction (Persia, AD c.1000), an elegant early example of an algorithm. The eponymous inventor of the algorithm, Al-Khwarizmi, was also a ninth-century Persian scholar — early algorists performed arithmetic by defining a set of rules on a system of variables used to represent Hindu-Arabic numerals.Also known as the decimal numbers.

How might one pursue this modest method further? Perhaps to develop a contemporary position that could go by the name of inhumanism. One might begin by uncovering the humanist position that dominates discourses on AI, no matter how covert its operation. Take the notion of technological singularity, the idea that AI surpassing human capacities will produce a runaway feedback loop leading to a crisis for humanity, on the surface a post-humanist vision. As suggested by Laruelle, there is a fundamental non-equivalence in the nature of cognitive acts we call intelligence, a non-equivalence exposed by our encounter with inhuman agency. François Laruelle, The Transcendental Computer: A Non-Philosophical Utopia, trans. Taylor Adkins and Chris Eby, see (https://speculativeheresy.wordpress.com/2013/08/26/translation-of-f-laruelles-the-transcendental-computer-a-non-philosophical-utopia/) The anthropocentric conceit of a singularity event is based on the implausible notion that all forms of intelligence are cognitive “performances” equally intelligible to us, a notion most famously dismissed by John Searle.John. R. Searle, “Minds, brains, and programs,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences, vol. 3, no. 3, (1980), pp. 417‒57. In singularity claims, this assumption of performativity is coupled with deep speculation that Turing machines can fully realize human minds, as if the first and only duty of AI should be to serve our rampant narcissism through isomorphism. Even in our own apocalyptic myths, humanism is exposed as the arbitration of reason by the human, a logos fumbling its way to its own crisis, its narcissistic nature revealed by the very imaginary of that collapse.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

If fidelity to a technological singularity reveals the hubris of a humanism stubbornly locating itself at the apex of reason, the theory of mind to which it appeals presents us with a far thornier landscape. The discourse on multiple realizability (MR) revolves around the claim that human minds can be instantiated on other substrates. Closer inspection reveals a field strewn with speculative models of mind drawing on various forms of functionalism, the early adherents of which (Hilary Putnam, Jerry Fodor) have abandoned many of their most striking claims.

Functionalism is a kind of systems theory of the mind, which insists that mental states ‒ be they concepts, intentions, or beliefs ‒ are characterized by the role they play within a system of reasoning. This position can be contrasted with physicalism, the scientistic notion that a reductive analysis will reveal all aspects of our minds in terms of neurobiological phenomena; or behaviorism, which reduces reasoning to a learned response to stimulus, with no recourse to higher order representations. Putnam, musing on his retreat from strong functionalism, considers the possibility of an algorithm that might explore the entirety of human discourse:

To ask a human being in a time-bound human culture to survey all modes of human linguistic existence – including those that will transcend his own – is to ask for an impossible Archimedean point.Hilary Putnam, “Chapter 5: Why Functionalism Didn’t Work,” in Representation and Reality. Cambridge, MA: Bradford Books, 1989.

This “Archimidean point” is precisely the impossible position taken up by humanism in the face of AI. Putnam’s implicit rejoinder to singularity follows a social account of reason, which makes it difficult to locate meaning in any one human mind, a socio-functionalism, which throws most MR claims into doubt. We can accept a situated functional theory of the brain, incorporating a representational model replete with concepts and beliefs, without indulging the fetish for a disembodied human consciousness. Inhumanism necessarily takes up such a functionalist account of reason rooted in symbolic representation, but must dispense with the dogmatic faith in multiple realizability; instead insisting on the non-equivalence of diverse realizations of intelligence.

To cleave reason from the sensible, to isolate it from environment and interaction, is to ignore the critical role of representation in reasoning, a picturing whose rules and norms Wilfrid Sellars plausibly claims are themselves situated.Wilfrid Sellars, “Some Remarks on Kant’s Theory of Experience,” The Journal of Philosophy, vol. 64, no. 20, Sixty-Fourth Annual Meeting of the American Philosophical Association, Eastern Division (1967), pp. 633‒647, here p. 642. Inhuman reasoning may require a revised theory of computation to capture this situatedness. Echoing Putnam’s social account of reason, the theory of interactive computing departs from the Church-Turing thesis, to explore computation as a process which takes input and output (I/O) into its core.Peter Wegner and Dina Goldin, “The Interactive Nature of Computing,” Minds & Machines Journal, vol. 18, no. 1 (2008), pp. 17‒38. In Church-Turing formalism, computation is what happens in between reading input and producing output. For interactive computation, I/O is intrinsic to algorithmic acts; it is constitutive of computation.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

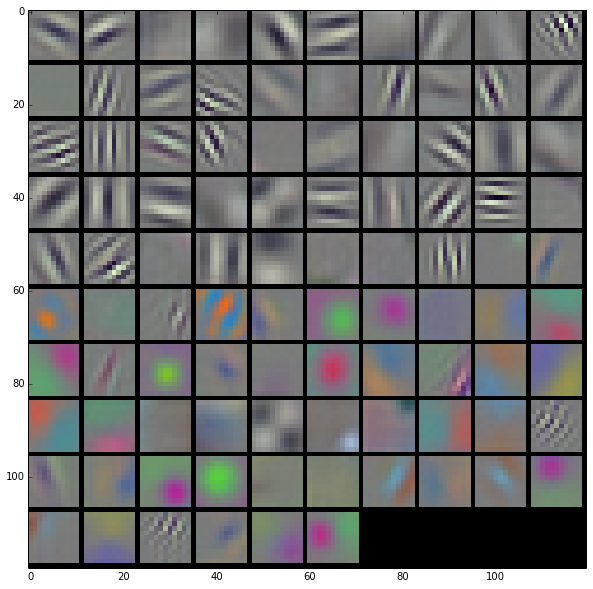

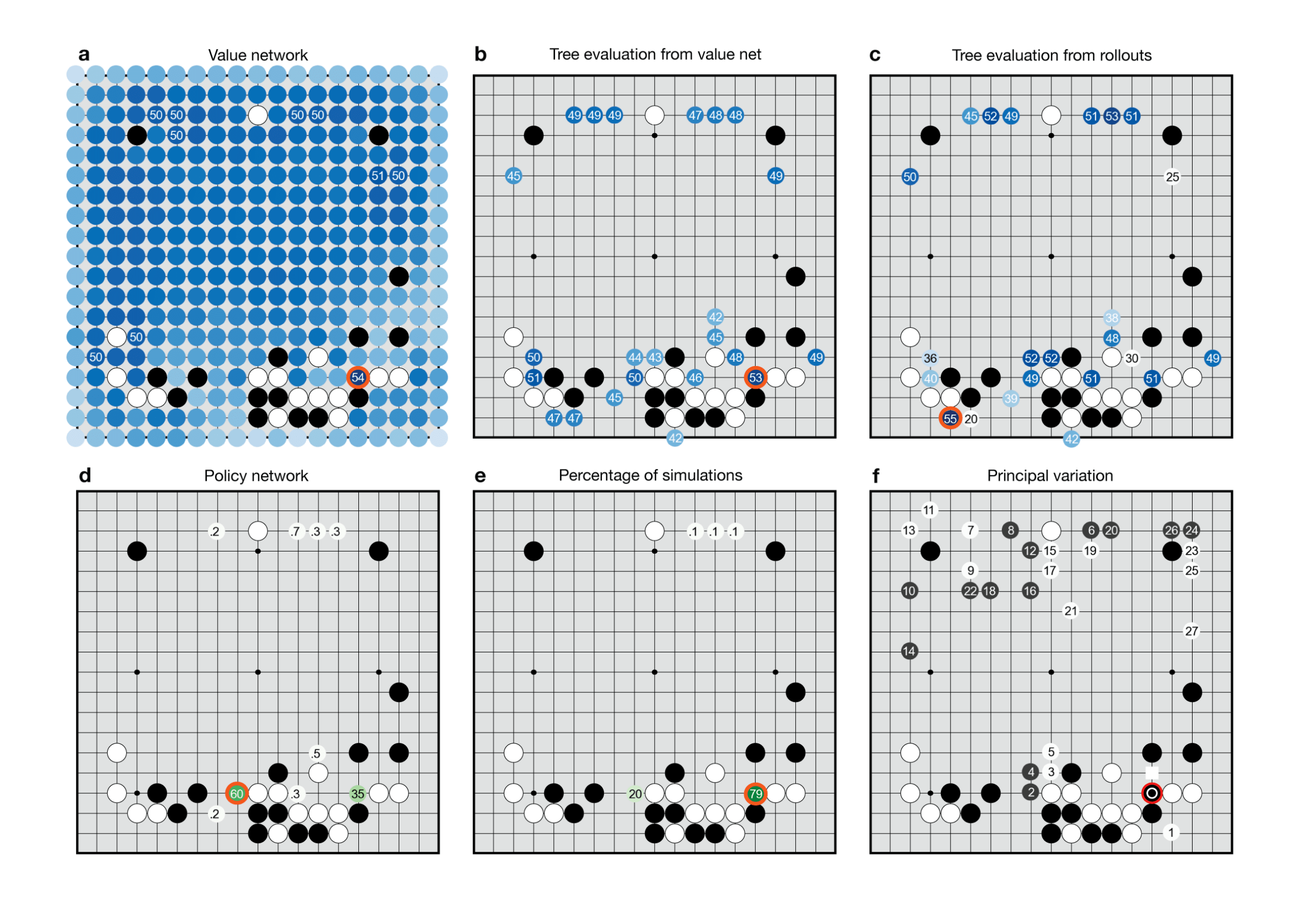

The interactive paradigm of computing best describes the contemporary status of algorithmic intelligence.Luciana Parisi, “Instrumental Reason, Algorithmic Capitalism, and the Incomputable,” in Matteo Pasquinelli (ed.), Alleys of Your Mind: Augmented Intelligence and Its Traumas. Lüneburg: Meson Press, 2016, p. 125. Most significant acts produced by computation today occur in a distributed, interactive environment, and increasingly algorithms significantly redefine themselves in light of new input. To take an example from deep learning, adversarial neural networks are pitched against each other in order to train—one takes on a generative role and the other a discriminatory one. Such adversarial techniques can be used to refine AI, for example two neural nets may play the ancient game of Go against each other. Their connectivity is effectively rewired through the adversarial back and forth, a learning process designed to optimize performance. This form of learning could be expanded to train larger groups of nets, in effect creating complex, emergent phenomena which continually rewire each net, coming closer to an interactive mode of inhuman reasoning.

If the situatedness of reason suggests interaction as a key to learning, what can we say of our interactions with inhuman forms of reasoning? In reality we can claim no more than a prehension of diverse intelligences, ever open to mistranslation at an epistemic level, the very real possibility of encountering the incommensurable at every turn. Take AlphaGo, the deep learning model which recently defeated a grandmaster at the game of Go. Its “eccentric” openings are now being actively studied by Go players worldwide,See (http://senseis.xmp.net/?AlphaGo). but this in no way guarantees human cognition privileged access to grasping its tactics (its reasons) in a meaningful way. A Go board of 19 x 19 cells can contain over 2 x 10^170 possible legal positions,See (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Go_and_mathematics#Legal_positions). a number greater than there are atoms in the observable universe.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Following Alain Badiou, we can say that every situation contains its own excess. This excess is strictly incommensurable, as there is no simple mapping between a set and its power set (the set of all its subsets). The proof of this comes from set theory and is known as Cantor’s diagonal argument. The power set expresses all the combinations of elements implied by a set—it unpacks all the possibilities contained within a given situation. In set theoretical terms, diagonalization reveals that the power set of an infinite set (e.g. the natural numbers) is of an incomparable size—in fact, there is an indivisible gap in size between the two sets, which nevertheless cannot be reconciled.This is known as the “continuum hypothesis.” This form of incommensurability is at play when prehending the inhuman space of reasons.

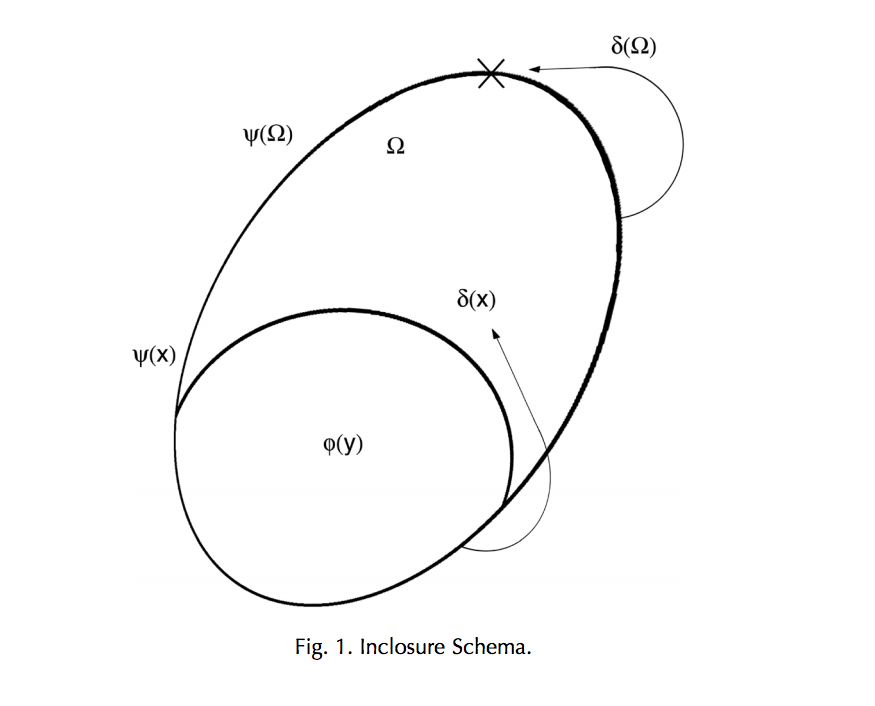

The proof of excess is a form of Cantor’s diagonal method, which is a specific case of what Graham Priest has called the Inclosure Schema, a logical template that describes various paradoxes situated at the limits of human thought.Graham Priest, Beyond the Limits of Thought. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2nd edition, 2003, p. 133. The scheme was first described informally by Bertrand Russell in 1905, having encountered a critical paradox in set theory, stated simply as “there exists a set of all sets that don’t belong to themselves.”Bertrand Russell, “On Some Difficulties in the Theories of Transfinite Numbers and Order Types,” Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Ser. 2, vol. 4 (1905), pp. 29‒53. Russell, “On Some Difficulties in the Theories of Transfinite Numbers and Order Types,” p. 142. The parent set both does and does not belong to itself, exposed as a contradiction precipitated by self-reference. Take as a discursive example of inclosure this formulation from Nāgārjuna, which dismisses the essence of things:

By their nature, the things (dharma) are not a determinate entity. Their nature is a non-nature; it is their non-nature that is their nature. For they have only one nature; no nature.E. H. Johnston and Arnold Kunst (eds), The Dialectical Method of Nāgārjuna (Vigrahavyavartani), trans. Kamaleswar Bhattacharya. Dehli: Motilal Banarsidass, 2nd edition, 1986.

Inclosure describes a paradox in which transcendence and closure are both asserted at once. A humanist account of rationality creates just such an inclosure of reason. Reflexive human rationality, casting itself in a transcendent position, claims to have purchase on all forms of reasoning. But through AI it unpacks a plethora of cognitive acts it claims to, but cannot fully, circumscribe. Put simply, the “space of reasons” (Sellars) may begin to multiply in ways the human cannot cognize.

How to resolve this inclosure of reason? Nāgārjuna’s solution would be to admit dialethism, the notion that statements can be both true and false at once, into our reasoning. We could embrace the contradiction and let it be. But an inhumanist approach would involve shifting perspective entirely. It would mean recasting the human as a mode of reason, which unpacks the rules of its own construction in a bootstrapping of its own reasoning. Such a process can only be undertaken from an inhumanist perspective, as AI represents this bootstrapping in effect—an encoding of reasoning which inevitably breaks out of the inclosure attempted by humanism.

Given this inhumanist perspective, how might we render the relation between human reason and categories such as AI? The question regards the possibility of surjection, which describes a correspondence relation in which each member of the co-domain is mapped by at least one member of the domain. Diagonalization, the method by which we reveal the excess of a situation, shows a correspondence between the two cannot be guaranteed if reason is considered an infinite set of hypotheses and theorems. The power set of theorems explored by AI would be of an incommensurable size and not reducible to human sapience. Human reason does not occupy the apex of rationality; rather, the latter is best described as an unpacking of reason by a thinking apparatus within an environment.

As Reza Negarestani asserts, inhumanism is an explicit commitment to just such a “constructive and revisionary stance with regard to [the] human.”Reza Negarestani, “The Labour of the Inhuman, Part 1: Human,” e-flux Journal #52 (2014) (http://www.e-flux.com/journal/52/59920/the-labor-of-the-inhuman-part-i-human/).

It commits to the unpacking of reason without taking out epistemic insurance, without a guarantee that the outcomes are intended for humans as such, but rather for intelligence itself as a vector of reason. It pursues a rationalist “middle way” that neither bemoans nor celebrates the dissolution of the human as the arbiter of reason, but takes its inevitability as a given — asserting, with Donna Haraway, that “we have never been human.”Donna Haraway, When Species Meet. Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2007, p. 11.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

So the question before us can instead be reformulated: Does the reasoning produced by AI lie within the jurisdiction of the human? Diagonalization casts severe doubt on this, while inhumanism remains deeply skeptical in matters of jurisdiction, having traded the static demarcation of “human” into the service of reason. Inhumanism regards AI itself as a misnomer—we need only be reminded by Jean-François Lyotard that humans did not invent technology, we are merely a specific “biotechnic apparatus,” no more “natural” than logic circuits etched into silicon.Jean-François Lyotard, The Inhuman: Reflections on Time. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992, p. 12. Within the technosphere all forms of reasoning are equally artificial, no privileged status can be reserved for organic beings.

Reason is not a perfectly rational system based on a disembodied system of rules. It operates instead as a plastic ensemble of self-referential representings, flawed and incomplete picturings of an environment put into ever-novel syntactic, semantic, and logical relations. Non-monotonic logic describes a reasoning that is able to revise its own axioms, to reconfigure its own ground rules in situ. The task for inhumanism is to develop, imagine, and engage forms of inhuman reason that are not merely productive of axiomatically guided agents obeying monotonic logic, not mere automatons of human bias, but rather of informal agents capable of what Luciana Parisi calls an “alien mode of thought.”Parisi, “Instrumental Reason, Algorithmic Capitalism, and the Incomputable,” p. 136. Following Sellars,Wilfrid Sellars, Some Reflections on Language Games, The Space of Reasons. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press, 2007, p. 28. reasoning is a metalogical game that reconfigures its own rules in light of a sensible world of things. Machinic intelligence without such a capacity will inevitably fail to revise its own axiomatic worlds or infer its own novel hypotheses, just as without sensory input it won’t prehend the data needed to form those representations that construct the singular becoming of reason. Machines will need a reason to think, as Lyotard reminds us:

The unthought would have to make your machines uncomfortable, the uninscribed that remains to be inscribed would have to make their memory suffer. Do you see what I mean? Otherwise why would they ever start thinking? We need machines that suffer from the burden of their memory.Lyotard, The Inhuman: Reflections on Time, p. 20.

Meanwhile the burden of our own memory weighs heavily. Turing should be added to that list of humiliations inflicted on the human, which we call modernity, traced from Copernicus to Darwin, Freud to Marx. With each humiliation comes its own unique trauma, but the decentering of our own rationality represents the endgame of enlightenment. It could be said that the best hope for modernity is for inhuman intelligence to escape its logos, to diagonalize out of its prescribed commitments, to construct its own alien logics. This might be the only solace we can offer for all those forms of agency cast as inhuman and assaulted to the point of annihilation by that project we call modernity.