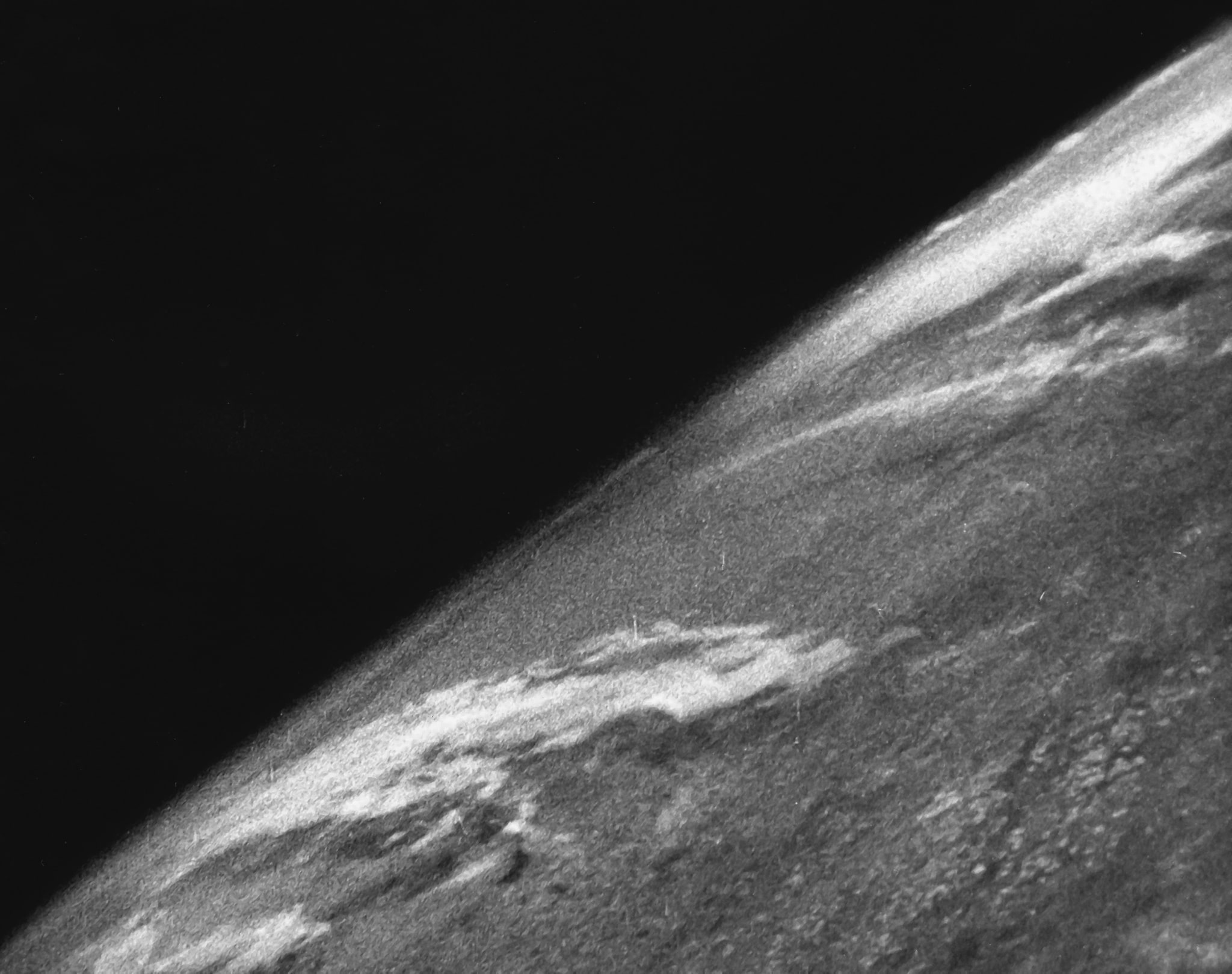

U.S. Army - White Sands Missile Range/Applied Physics Laboratory 1946

Technosphere Verticality

With satellites and their debris now orbiting the planet, it serves to explore this beyond-stratosphere infrastructure and how it monitors the technosphere’s more terrestrial happenings. Environmental historian Johan Gärdebo introduces us to this outermost layer of the technosphere and discusses the consequences of such verticality in “environing” the Earth.

Since Sputnik, thousands of satellites have circled the Earth in ninety-minute orbits. Their electromagnetic waves now envelop the globe in a second atmosphere, a technosphere [my italics]. The dense network of data gleaned from satellite observations, and the heavy computer infrastructure enabling this to be processed, are both part of the solution [. . .] and part of the problem.Christophe Bonneuil and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, The Shock of the Anthropocene: The Earth, history and us, trans. David Fernbach. New York: Verso, 2016, p. 61.

The technosphere is a term conceptualized by Peter Haff as the systemic proliferation and perpetuation of technology. “Systemic” refers both to the set of rules by which humans are incorporated as subcomponents in the expansion of the technosphere and how, subsequently, technologies are interconnected with other technologies – and these human subcomponents – in a horizontal movement of energy and matter across the Earth’s surface.Peter Haff, “Humans and technology in the Anthropocene: Six rules,” The Anthropocene Review 1, no. 2 (2014): pp. 126‒36. Barry Commoner has also offered a similar conceptualization of the technosphere as the consumption by man-made processes across the planet’s natural environment. The power of technology was “painfully self-evident” in nuclear power plants, synthetic plastics, and chemicals for fast-growing crops that fuel overpopulation. The technospheric flow of energy and matter do not alleviate; they perpetuate societal needs on the natural system while at the same time deteriorate the habitat on which human life depends.Commoner’s concept of “environment” divides nature into a natural ecosphere and a man-made technosphere that require a more rational and just use of both environments, cf. Barry Commoner, The Closing Circle: Nature, man and technology. New York: Knopf, 1971, p. 293; Commoner later developed the concept, arguing that the technosphere has become “sufficiently large and intense to alter the natural processes that govern the ecosphere. And in turn, the altered ecosphere threatens to flood our great cities, dry up our bountiful farms, contaminate our food and water, and poison our bodies [. . .] diminishing our ability to provide for basic human needs.” See Barry Commoner, Making Peace with the Planet. New York: Pantheon, 1990, p. 7.

The quote above by Christophe Bonneuil and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz serves, however, to shift the basis of the technosphere’s horizontal emphasis toward the orbital layer of satellites and debris that constitutes the technosphere’s vertical expansion ‒ the vertical expansion through an orbital layer of satellites. Below, I will describe why satellite observation of Earth is a technology that represents the technosphere while at the same time it is a technology that makes representation of the technosphere possible. Firstly, the technosphere has expanded vertically into outer space where it currently constitutes an orbital layer of satellites and debris. Secondly, the satellites of the orbital layer collect data about the Earth’s surface, which over time form the digital layers of present and the past shape of the planet. The data is vertical in the sense that users can reach down in time to see what the Earth’s environment used to be. And thirdly, satellite data and debris together illustrate how the knowledge of the technosphere is a consequence of its own physical expansion.

SPATIAL VERTICALITY

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Illustrating the technosphere’s expansion requires that technology be considered through representations of the technosphere as an infrastructural or networked whole. Examples of these are gas pipelines, intercontinental food freighting, and instant communication using an Internet connection. If the technology is networked into a flow of energy and matter, it is not only a thing unto itself but also represents a systemic component of the technosphere.Peter Haff, “Technology as a Geological Phenomenon: Implications for human well-being,” in Colin N. Waters, Jan Zalasiewicz, and Mark Williams et al. (eds), A Stratigraphical Basis for the Anthropocene. London: Geological Society, Special Publication 395, 2013, p. 2. The horizontal movement of technology across the Earth’s surface demonstrates both the magnitude of systemic interconnections and, correspondingly, the difficulty of distinguishing human agency in the extraction of energy and matter when the expansion spans great distances with effects on several environments.

Humans are users of interconnected technologies, but even more so they are dependants within this interconnection. One may be aware that transportation, heating, and consumption contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. And one may be aware that the nutrients and residue of food does not return to where these were first harvested. But can usage, agency, or accountability of these systems be attributed to any single group of people, a company, or a country? Previous efforts to distinguish agency have done so by analyzing one particular component, like cell phones for example, that then rise above the rest of the flows with which they are entangled across the Earth’s surface. Continuing the cell phone example, one could follow the devices through the mining of their minerals, assembly in factories, dissemination by transnational retailers, and eventual disposal in junkyards.A cradle-to-grave approach has been used to study flows of energy and matter vertically in the mining, production, and dissemination of digital data and debris on the surface of the Earth. Cf. Jennifer Gabrys, Digital Rubbish: A natural history of electronics. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2011; Armin Reller, Materials Critical to the Energy Industry. An introduction, Augsburg: University of Augsburg, 2012; Volker Zepf, Rare Earth Elements. A new approach to the nexus of supply, demand and use: Exemplified along the use of neodymium in permanent magnets. Berlin et al.: Springer, 2013. Analyzing these components is important for demonstrating the agencies involved in creating the layers and sediments of the technosphere. I propose that understanding artificial satellites in a similar mode provides a clear illustration of both the agency involved in the technosphere and its vertical expansion, not only into the depths of the Earth but toward the orbital space above the Earth’s surface.

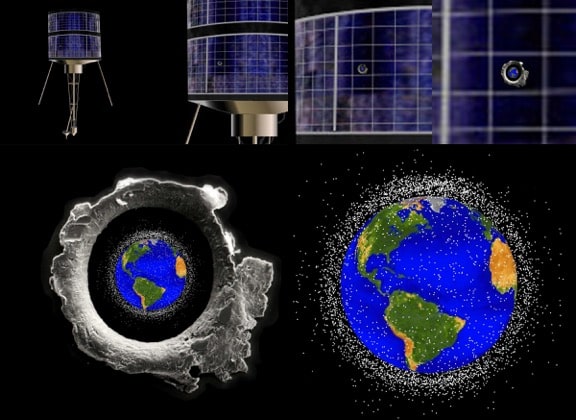

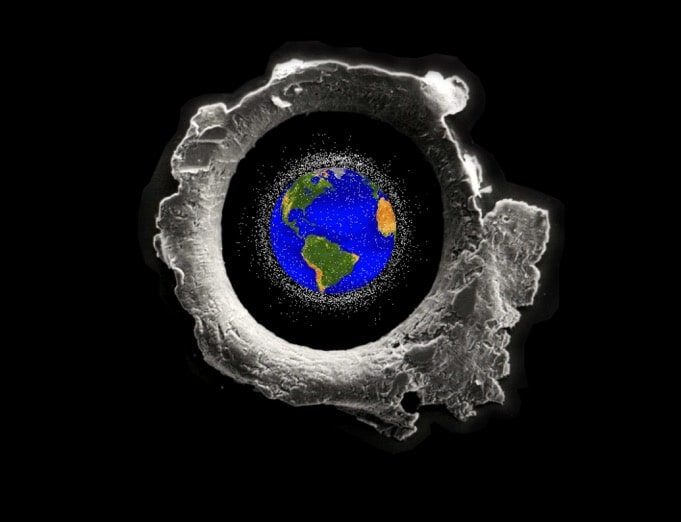

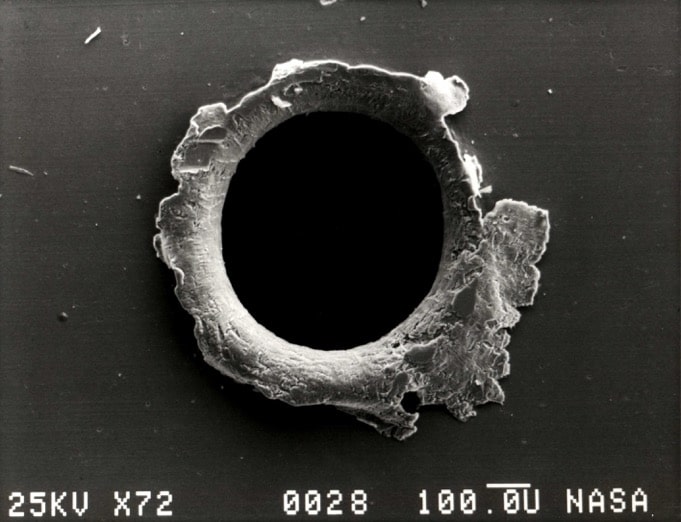

The Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik-1 in 1957 was the first addition to an orbital layer. The number of satellites increased rapidly thereafter, initially as part of the Cold War arms struggle as it extended into outer space and then later becoming an operational system that linked the various satellites for the collection of data about the Earth’s surface. By 2015, nearly sixty years after the launch of the first satellites, there were more than 17,000 space objects, of over ten centimeters in size, in orbit around Earth. The vast majority of these objects are exploded rocket stages, droplets of coolants, and components of no longer functional satellites as a result of disintegration and collisions. Of the 4,060 satellites in orbit some 1,400 are operational.Sven Grahn and Kristina Pålsson, Lärobok I Militärteknik, Vol. 7: Rymdteknik [Curriculum I. Military technology: Space technology]. Stockholm: Försvarsmakten (Swedish Armed Forces), 2007. Heiner Klinkrad, Space Debris: Models and risk analysis. Berlin et al.: Springer, 2006.

The United States, Russia, and the People’s Republic of China launched most of these satellites. While over fifty countries have built satellites, only eleven nation-states own the necessary facilities to launch them. Nation-states that use satellites expanded their numbers based on political priorities that have preserved asymmetrical power relations in terms of who can utilize outer space.Lisa Parks and James Schwoch (eds), Down to Earth. Satellite technology, industries and cultures. Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012, pp. 3, 222. These orbital asymmetries have their corollaries in the horizontal establishment of satellite systems on the Earth’s surface; such as launching sites and receiving stations for satellite data. The nation-states of France and Sweden established satellite facilities in regions peripheral to their political centers. France used the former slave colony of French Guiana in northeastern South America as a launching pad for French, European, and later international commercial use.Peter Redfield, Space in the Tropics: From convicts to rockets in French Guiana. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000. Since the mid-twentieth century, Sweden has established a rocket facility within the indigenous Sami people’s pasturelands in the north of the country; a site that was later expanded for the commercial downlinking of data from satellites whose orbits converge near the poles of the Earth.Fredrick Backman, Making Place for Space. A history of “Space Town” Kiruna 1943‒2000. Umeå: Umeå University, 2015.

The installations mentioned here constitute only a portion of the growing satellite infrastructure. Here they serve to illustrate how outer space is utilized as part of industrial and political collaborations in sectors of society other than those with which the technological systems are involved.John Krige, American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006; John Krige, Arturo Russo, and Lorenza Sebesta, A History of the European Space Agency 1958‒1987. Vol. II: The Story of ESA, 1973‒1987. Noordwijk: ESA Publications Division, 2000. As orbital space is increasingly littered with satellite debris, we face similar questions to those surrounding the horizontal flows of energy and matter of agency – who is accountable for the debris? Orbital debris differs from their grounded counterparts since ‒ given the scale and cost of implementing them ‒ one can inquire into who assembled, launched, and used the satellites. The agency involved in the technosphere is thereby identifiable to specific peoples, companies, and countries whose actions vertically expanded an otherwise horizontal technosphere. And as outer space is increasingly filled with things from the horizontal technosphere below, one may know the system as a whole by observing its orbital parts.

TEMPORAL VERTICALITY

large

align-left

align-right

delete

One could have envisioned most of the Earth’s orbital space as a void of things had humans not begun launching artificial satellites. But on a corresponding note, it would be hard to envision the technosphere as a concept without readily available data from the satellites orbiting Earth. Satellites, like the technologies with which they are interconnected, represent the technosphere as a whole – pars pro toto. Following a satellite’s assembly and disposal as debris is a means by which to consider the agency of an entire infrastructure. But the spatial verticality that represents the technosphere also has a temporal verticality that provides the technosphere as a representation. Satellite observation is a representation technology; satellites collect data necessary for systemic depictions of Earth from above.

As satellites collect layer upon layer of data, a temporal verticality develops whereby one can sense both present and past surfaces of the Earth. Paul Edwards has demonstrated that a global world-view can be interacted with operationally once a knowledge infrastructure is established, of which sensing, processing, and dissemination of satellite data is one of the more recent forms. The knowledge infrastructure includes, here naming a few, technicians, policy-makers, and authorities who develop procedures, productions, and practices for society’s interpretation of the world. Grasping the idea of an Earth system, Edwards argues, is a functional effect of that vast infrastructure which, in its flows of energy and matter, has global reach. We know about environmental changes in that global system because there is accessible data that demonstrates how it used to be as compared to the current state. It is when you descend vertically into previous layers of data that you are able to perceive of the Earth’s global environment, providing scientific analysis and formulating ethics for its use.Paul N. Edwards, A Vast Machine: Computer models, climate data, and the politics of global warming. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010, pp. 6‒9, 22‒3 ; cf. Jennifer Gabrys. Program Earth: Environmental Sensing Technology and the Making of a Computational Planet. Electronic Mediations 49. University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

In order for satellite observation to represent the Earth’s global environment, the data developed from the technically possible into the politically probable and, lastly, into the institutionally practical. Regarding that which was technically possible, Sebastian Grevsmühl illustrates how satellite observation acquired an environmental rationale as a serendipitous outcome of surveillance. By the late 1960s, satellites produced a “surplus” of electro-optical data far exceeding what could be used for military purposes. Among the surplus of data were observations of regional deforestation, receding glaciers, and advancing droughts. Satellite observation was used to monitor the environment from the late twentieth century onwards because that was when it was technically possible.Sebastian Grevsmühl, “Serendipitous Outcomes in Space History: From space photography to environmental surveillance,” in Simone Turchetti and Peder Roberts (eds), The Surveillance Imperative. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, pp. 171‒2, 186; Sebastian Grevsmühl, La Terre vue d’en haut. L’invention de l’environnement global. Paris, Le Seuil, 2014. However, in order to make satellite observation politically probable, as Jason Beery demonstrates, the United States and other satellite-launching nation-states negotiated within the United Nations about the use of outer space for earthly environmental concerns. Western countries framed satellite sensing as a sensible thing for the preservation of ecosystem services, which several developing countries, the Soviet Union, and the non-aligned states, opposed on the grounds that satellite sensing was also a means to survey and exploit those ecosystems.Jason D. Beery, Constellations of Power: States, capitals and natures in the co-production of outer space. The University of Manchester, 2011; Jason Beery, “Unearthing Global Natures: Outer space and scalar politics,” in Political Geography. Forthcoming, 2016; cf. James Ormrod and Peter Dickens (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Society, Culture and Outer Space. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. Satellite observation according to Michel Avignon and co-authors became institutionally practical in the 1980s when United States and European efforts to commercialize data processing increased training and equipment that users could interact with and which make global data sets operational. The layer upon layer of data could be treated as part of the Earth’s environment once that global world-view was institutionally practical.cf. Michel Avignon, Cathy Dubois, and Philippe Escudier (eds), Observing the Earth from space. Malakoff: Dunod, 2014, p. 224.

Timothy Luke argues that the increasing number of references to the “environment” from the 1970s onward corresponds with the growing number of technologies that provided global world viewing, or world watching. The etymology of “environment,” Luke suggests is an English term borrowed from the Old French where the word environment is the product of a verb, “to environ.” Environing is a strategic action to physically encircle something, for example, by stationing guards around or watching over a person or place.Timothy Luke, “On environmentality: Geo-power and eco-knowledge in the discourses of contemporary environmentalism,” Cultural Critique 31 (Fall, 1995): pp. 57‒81; see also the previous version of this argument in Timothy Luke, “Beyond Leviathan, beneath Lilliput: Geopolitics and glocalization,” a Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association of American Geographers, Atlanta, GA, April 7‒9, 1993. According to Sverker Sörlin and Paul Warde, environing links social action with frequently used separations of nature and society.Sverker Sörlin and Paul Warde, “Making the Environment Historical ‒ An Introduction,” in Sörlin and Warde (eds), Nature’s End: History and the environment. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, p. 21. Environing refers, in this case, to a practice that co-produces nature along with society. Human agency operates within and makes the environment through everyday practices, and awareness about these practices involves many other things beyond their environmental implications. Joachim Radkau suggests that environmental awareness, for this very reason, should be analyzed in relation to other ongoing motivations; the environment happened while one was doing other things.Joachim Radkau, Nature and Power: A global history of the environment. London and Cambridge: German Historical Institute in London and Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 323. This is a co-production that flows from nature outside humans to nature within humans as well as across several landscapes.Joseph Masco, “Bad Weather: On planetary crisis,” Social Studies of Science 40, no. 1 (2010): pp. 7‒40; James Fleming, Fixing the Climate. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010. But as demonstrated earlier in the discussion about how satellites and debris constitute the spatial verticality of the technosphere, the satellite data is a co-production that emphasizes human agency in the temporal verticality of the technosphere. The temporal verticality is important since it allows interaction with the system whose aesthetic scale provides a planetary view. Whereas the matter of the technosphere is at a scale so great humans cannot be distinguished on it, the flow of data is where humans make the technosphere knowable. At the operative scale of an interface whereby satellite observations are used to understand the technosphere, humans and the planetary system do then share size.

VERTICALITY EMPHASIzES THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HUMANS AND THE TECHNOSPHERE

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Hanna Arendt wrote shortly after the launch of the first satellites that the conquest of space would make the triumph of scientific man short-lived. Seeing humans as but one of several components of Earth erases the species’ exceptionalism once humans are equated with what used to be their surroundings. Now humans were a part of the environment. And observing Earth from outer space, Arendt argues, is a choice dictated by Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle whereby human observation determines one aspect of nature while blurring or altering another.Hanna Arendt, “The Conquest of Space and the Stature of Man” (1963), reprinted in The New Atlantis: A Journal of Technology and Society (2007), p. 52. The argument so far is that a vertical expansion of the technosphere constitutes data collected in order to provide a world-view of a global environment or Earth system and that this systemic knowledge, in turn, produces debris throughout the environment that is orbital space. The environing activities whereby the technosphere is envisioned, also enlarges it, eliciting the question of how the sensing and shaping of the technosphere are connected and how this allows us to interact with both its data and debris.

But why is the view from above different from how humans have otherwise perceived, or not, the world as a system and a global environment? There are several counterarguments to be made based on previous vertical efforts, depictions, and intuitions of the world. First, a world-view from above is not confined to satellites or indeed any vertical medium as such. William Fox argues that an aerial view of reality, “aereality,” has been fundamental to human survival. In extreme or arid landscapes, where points of reference are few, the grounded view of human sight is to produce an operative sense of place from above, an aereality. Artists and cartographers producing maps were adapting more than they were constructing aereality, which is something that humans have been making use of long before technoscientific enterprise or the military-industrial complex funded and made prominent a world-view from above.William L. Fox, Aereality: Essays on the World from above. Berkeley, CA: Publishers Group West, 2009, pp. 3, 10, 223. As for the conceptualization of Earth from above, Kerry Magruder attributes the circulation of a global imagery to the proliferation of new mediums in the 1700s, most notably cheaper printing techniques for books. Illustrations of Earth allowed several disciplines to converge and correspond as to how to depict a planetary reality and form subsequent debates about science and ethics for life in a global world.Kerry Magruder, “Global visions and the establishment of theories of the Earth,” Centaurus 48, no. 4 (2006): pp. 253‒4. Both Magruder and Fox rely on Denis Cosgrove’s scholarship of how Western states and scientists in particular asserted authority over and through aerial views.Denis Cosgrove, Apollo’s Eye: A cartographic genealogy of the Earth in the Western imagination. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. In the work of Fox, Magruder, and Cosgrove there is nothing to suggest that satellites would shift human perception of Earth, nor one’s place within that global environment or system. Satellites could be considered just another medium to adapt human aereality in a longer tradition of technoscientific military enterprise.

There is also the prospect that the environing of Earth is cultural. Lisa Parks argues that the Western use of outer space simulated the global Earth before there was technical capacity to produce any global data sets. Television series like the 1960s international Our World constructed a live-broadcast feel that, via satellites, could switch between different locations around the world. Parks concluded that programs in the same vein as Our World asserted fantasies of Western culture in order to later acquire a synoptic view and presence in outer space before this was technically possible.Lisa Parks, Cultures in Orbit: Satellites and the televisual. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005.

Each of these points of criticism deserves further study on how humans perceive the environment, but the technosphere’s verticality, its data and debris, offer a historically novel approach to how humans interact with a global environment regardless.

Here it is as well to remember Yi-Fu Tuan’s account of how physical science, aesthetics, and architecture and, thereby their perceptions of environment throughout various cultures, began by the late 1700s to shift from vertical to horizontal expressions. Vertical landscape elements evoked a sense of striving, a defiance of gravity, while the horizontal elements were easier to incorporate into planning and rest. One example is the European horizontal organization of nature into spheres that unfold across the Earth’s surface of which the hydrologic cycle became widely circulated to explain transportation of matter and energy from land and sea.Yi-Fu Tuan, Topophilia: A study of environmental perception, attitudes, and values. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1974, pp. 28, 134. The previous vertical model from Aristotle’s Meteorologica is a cosmos where water transforms into other elements; a model that sought to pedagogically translate the transcendental relationship existing between the human soul and God, where the soul is a water droplet seeking absorption into heaven or, in other cases, God as the rain that brings back sustenance to the souls of a parched Earth. As the hydrologic cycle acquired its horizontal dimension it became a physical process that did not retain previous metaphoric powers or symbolic overtones.Yi-Fu Tuan, The Hydrologic Cycle and the Wisdom of God, Department of Geography Research Publication No. 1. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1968.

As a physical environment is expanded and manageable horizontally, there are no indwelling spirits of that nature mirrored in a vertical cosmos transcending the immediate landscape.Tuan, Topophilia, pp. 148, 245. In this open horizontal space, the technosphere will always be larger than any human interacting with it. Human agency in a physical environment is also hard to perceive, because the horizontal notion assumes that the environment as something apart from the humans within it. But it has already been illustrated how humans contribute to the spatial verticality of the technosphere through the launch of satellites and debris into outer space. And it has already been suggested how data from satellites provides knowledge of a global environment with which humans can interact and know the technosphere. As a horizontal concept, the technosphere is a rich description of energy flows. But with inference from Tuan’s analysis, the technosphere requires more sophisticated formulation of its vertical elements in order to serve as a metaphor ‒ both transcendental and symbolic – for human meaning, agency, and activity. In order to know oneself, humans in the technosphere need to gaze up to the vertical life into which the technosphere has expanded, and from which humankind made a view of the technosphere possible, probable, and practical.